http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.383

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Presentation of the Multidimensional Couple: Socioemotional Impact Scale

Presentación de la Pareja

Multidimensional: Escala de Impacto Socioemocional

Raúl Medina Centeno1*,

Sara Menéndez-Espina2,3, José Antonio Llosa3, Esteban

Agulló-Tomás3

1 University

of Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico.

2 University

Isabel I, Burgos,

Spain.

3 University

of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain.

* Correspondence: anaram81@gmail.com

Received: December 11, 2023 | Revised: February 29, 2024 |

Accepted: March 18, 2024 | Published Online: March 25, 2024.

CITE IT AS:

Medina, R., Menéndez-Espina, S., Llosa,

J., & Agulló-Tomás, E. (2024). Presentation of the Multidimensional Couple: Socioemotional

Impact Scale. Interacciones, 10, e383. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.383

ABSTRACT

Introduction: A systemic instrument is presented to measure

the socioemotional network in relation to the partner and the person's

perception of the impact of this intimate network on his or her partner for his

or her classification. It is based on the idea that a nurtured social network

brings positive benefits to one's nuclear partner. In order to verify this

assumption both in research and in clinical practice, it is necessary to

construct a complex instrument that allows reaching different dimensions within

and outside the couple. Objective: The study seeks the construction and

validation of the Multidimensional Couple scale to measure seven dimensions in

the couple: emotional, cognitive, physical interest, protection, trust, respect

and power, as well as an additional dimension to classify the type of couple. Method:

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Exploratory Factor Analysis (CFA) were

carried out to test the psychometric properties and the adequacy to the

theoretical model. A total of 1149 people (71.5% women and 28% men) living in

Mexico participated. Result: The presence of a scale formed by 7

dimensions in the couple and a second order factor is confirmed, which can be

applied both by adjusting the answers to the couple itself and to other people

different from the couple. The goodness-of-fit and reliability indices are

satisfactory. Conclusion: This scale provides a psychometric instrument

that allows the study of the relationship between the couple.

Keywords: One-dimensional couple, Multidimensional couple, Relationship nutrition,

Validation, Couple relationship.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Se presenta un instrumento de origen sistémico para medir la red

socioemocional en relación con la pareja y la percepción de la persona sobre el

impacto de esta red íntima en su pareja para su clasificación. Se parte de la

idea de que una red social nutrida aporta beneficios positivos en la propia

pareja nuclear. Para la comprobación de este supuesto tanto investigación como

en la práctica clínica, se hace necesaria la construcción de un instrumento

complejo que permita alcanzar diferentes dimensiones dentro y fuera de la

pareja. Objetivo: El estudio

busca la construcción y validación de la escala La Pareja Multidimensional para

medir siete dimensiones en la pareja: emocional, cognitiva, interés físico,

protección confianza, respeto y poder, así como una dimensión adicional que

permita clasificar el tipo de pareja. Método: Se ha llevado a cabo un Análisis Factorial Exploratorio (EFA) y Análisis

Factorial Exploratorio (CFA) para comprobar las propiedades psicométricas y la

adecuación al modelo teórico. Participó un total de 1149 personas (71.5%

mujeres y 28% hombres) residentes en México. Resultados: Se confirma la

presencia de una escala formada por 7 dimensiones en la pareja y un factor de

segundo orden, que se puede aplicar tanto adecuando las respuestas a la propia

pareja como a otras personas diferentes a esta. Los índices de bondad de ajuste

y de fiabilidad son satisfactorios. Conclusión:

Con esta escala se aporta un instrumento psicométrico que permite

estudiar las diferentes dimensiones de la pareja y cómo estas se alimentan en

base al establecimiento de relaciones con personas ajenas a la misma.

Palabras claves: Pareja unidimensional, Pareja multidimensional, Nutrición relacional, Validación,

Relación de pareja.

INTRODUCTION

The couple entails a semantic and meaning complexity that makes it

impossible to define it with syntactic brevity. However, the couple is

multi-determined by psychological, interactional, social, political, historical,

religious, cultural, material and emotional factors (Mora et. al, 2017; Stange

et. al, 2017).

The concept of couple has been the subject of study and interest by

social and human disciplines (Benavides, et al. 2021), it can be said to be a

complex system in constant change (Stange et al., 2017). They all agree that,

in each culture and historical period, there are different ways and forms of

being and establishing relationships as a couple (Castañeda, 2016; Mora et. al,

2017; Stange et. al, 2017, Rodríguez, 2019).

Despite the fact that the couple is recognised

as a complex and multi-determined system, it is notable that it is not

approached, understood and measured, considering the different actors, systems

and cultural elements that impact, determine and configure it. In short, it

seems that at a theoretical level the couple o marriage is thought of as a

system produced in relation to the context, but methodologically and

operationally, it continues to be measured and approached as a closed and isolated

system. In this sense, it is relevant, as Jondec

(2020) points out, that experts on the subject conceive, measure and approach

the couple considering the changing and uncertain context in which it exists.

Also, their network of links, since the couple's surrounding world has a

bearing on their values scales, levels of satisfaction, desires and

expectations, even frustrations and conflicts.

The title of this instrument is inspired by Marcuse's (1964) concept of

the one-dimensional man is taken here as a conceptual metaphor to refer to the

couple, in particular the traditional heterosexual couple as the only one that

provides well-being and security to its members.

With the above, the need arises to create an instrument to measure

relational complexity, from an ecological approach (Bateson, 1973). This

instrument is not aimed at a particular type of couple or gender. as the

analysis focuses on the socio-emotional relationship however, the way of being

or existing in a couple.

This instrument makes visible and shows that today, even in traditional

societies, the one-dimensional couple is a myth. Contemporary couples are

multidimensional. The general thesis that is defended is that this

multidimensional-emotional universe of the person - beyond the couple and

family - contributes qualitatively to personal well-being and in a triangular

way to the couple’s relationship (Scheinkman, 2019).

Thus, building what is here called the multidimensional couple: those

non-family members who make up a significant and intimate relational system

that influences the couple's relationship.

Measuring the multidimensional couple

Among all the instruments, multidimensional or not, few make reference

to the non-familial relational context of the partners as part of couple

satisfaction and adjustment (Arias-Galicia, 2003; Barón,

2002; Díaz-Loving & Armenta, 2008; Flores, 2011; González et al, 2004;

Hendrick, 1988; Ibáñez et al., 2012; Iraurgi et al.,

2009; Larson & Bahr, 1980; Lauer et al., 1999; Locke & Wallace, 1959;

Olson & Wilson, 1982; Pick and Andrade, 1988; Pozos et al., 2013; Roach, et

al., 1981). None of them consider it a fundamental factor for the

transformation and recognition of their satisfaction. In this breadth of

instruments, the lack of approaches that consider the social environment of the

couple stands out. Of the few that exist, Graham (2000) stands out as a reference

by including the social support variable in the conception of couple

satisfaction. Also, Kaufman and Taniguchi (2006), who showed a positive

relationship between the network of friends and partners and marital

satisfaction. On the other hand, in a research study, Antonucci, et al. (2001)

describe the positive and negative impacts of the friendship network on the

couple's relationship, without explaining what these impacts are due to.

The multidimensional couple focuses on measuring the non-familial personal

socio-emotional network of people who live as a couple, especially those with

whom a certain intimacy has been generated, understood as: “any form of close

association in which the person […] acquires a shared detailed knowledge… a

privileged knowledge of one that no one else has […] a degree [of] emotional

understanding that implies a deep look inside the self” (Tenorio, 2010. p.65).

In other words, intimate relationships have to do with affective support,

supportive dialogue, the ability to talk about personal and profound things,

trust and security felt with the other (Maureira,

2011). The Multidimensional Couple bases its logic on the belief that one plus

one equals three (Caillé, 1992). In other words,

triangular, non-familial relationships are a significant socio-emotional

referent that directly influences the couple’s relationship and allows us to recognise the specific relational patterns that are

classified.

The couple as a triangular relational system: the socio-emotional

dimensions of measurement

This instrument is based on the systemic-ecological model, especially

the perspective proposed by Bateson (1973), that incorporates culture and

nature from an ecological dimension. Thought, feelings, and rationality are

rooted in the ecosystem, so the couple; it is seen as a recurrent system that

is constructed in their circular relationship with each other and other systems

where they coexist.

This instrument focuses on positive relational triangulation, the couple

seen as a triangle as an alliance are a path of growth to become emotionally or

cognitively closer to a third person, establish bonds, redefine or re-signify

relationships, influencing the identity and well-being of the person (Haley,

1980). In this respect, Caillé mentions that "from

a systemic perspective, every human system [in our case the couple] appears as

a set of individuals plus a symbolic «third party», which represents the organisational model of the system more or less consciously

shared by these individuals" (1992, p.88).

Linares, following the systemic tradition who focused on the family as a

primarily emotional system, proposes the concept of relational nourishment. He

speaks of socio-emotional nourishment as the subjective experience of being

loved and supported, that is, of being the object of loving thoughts, feelings

and actions (Linares, 1996; Linares, 2012).

Linares' model breaks down seven conceptual dimensions that we consider

basic to recognise the triangular socio-emotional

relationships of the couple. Each of them takes up a dimension of the

relationship that will be studied in detail, by means of specific questions

that qualify the relational pragmatics of everyday life:

·

Emotional dimension: This is divided into two concepts: Feeling

accepted: Admitting the other person's individuality, their being, and

validating it in a genuine way. This full acceptance implies living with it

without wanting to change it, without doing anything to modify it (Higuera,

2006). In Maturana's terms (1997), making the other feel legitimate, just like

oneself. And, on the other hand, feeling loved is the subjective experience of

feeling loved, that we have affection, will or inclination (Quees.la, 2013,

Linares, 2012).

·

Cognitive dimension. This block is divided into feeling recognised, which is the confirmation of the existence of

the other at a relational level. In other words, the existence of the other

entails full autonomy, with his/her own needs that are different from my own

(Linares, 2010; Linares, 2012). And feeling valued, which means appreciating

the qualities of the other, even if (or precisely because) they are different

from one's own (Linares, 2010; Linares, 2012).

·

Physical attraction dimension. On the physical dimension, it refers to

feeling attractive in the eyes of the other person and, on the other hand,

feeling seduced and attracted by the one who provokes desire.

·

Support dimension. Support and protection are the experience where the

other person participates closely in our life. It is to be under their care and

interest. The counterpart is attentive to our needs and provides us with what

is necessary for us to be well (Oxford Dictionaries, 2016; Real Academia

Española, n.d.).

·

Respect dimension. This dimension identifies whether the person feels

that he/she is treated with consideration, taking care at all times of the

limits that lead him/her to feel safe (Real Academia Española, n.d.).

·

Power dimension. The power dimension, which we translate into feeling

admired, means appreciating that the other values us in a very positive way for

our qualities (Oxford Dictionaries, 2016; Real Academia Española, n.d.). This

is an everyday act where the gaze and recognition of the other for my qualities

annihilates any power play that destroys love.

·

Trust dimension. This is considered to be the foundation of the

relationship, the cement that holds the couple together and allows differences

and discrepancies to be tolerated (Núñez, et al., 2015). It is defined in

general terms as the firm certainty or absolute belief that I or my partner act

and will act appropriately, in accordance with the implicit or explicit

commitments that define the relationship. Acting contrary to this is considered

betrayal.

In summary, each of these dimensions is analysed

from the perception and feelings of the person who applies the questionnaire in

relation to their own partner and their intimate (non-family) network, with the

aim of making visible the significant socio-emotional network by dimension and

in its totality; which forms part of their own and their partner's well-being.

At the end, another ten questions are organised

transversally to the seven dimensions, from a triangular logic that will allow

us to measure the impact of this significant socio-emotional network that the

person believes has on his/her partner. With this, the type of partner they

currently have is categorised.

Classification and contemporary studies of the couple

·

The flexible complementary traditional couple: Its distinction lies in

the fact that the traditional distribution of roles takes place within a

framework of mutual respect and recognition, but can alternate with symmetrical

patterns in the distribution of roles (Watzlawick et al. 1976).

·

The rigid traditional couple: In this couple, the roles are traditional,

but there is an explicit dominance over the spouse assumed as weak (Watzlawick,

et al., 1985). Linked to the imaginary of the patriarchal family (Benavides, et

al. 2021; Mora et. al, 2017, Medina, 2013, Medina, 2018, Medina, 2022a), in

this couple the psychological or physical abuse by the man towards the woman

stays within the home. These couples have become more complex due to the

incorporation of women into the labour market. This

led to an increase in working hours for these women, working inside and outside

the home. Generating what is now known as "double shift " (Hochschild

and Machung, 1989; Menéndez-Espina, et al., 2020) or

double presence (Balbo, 1994), carrying an excessive burden. It is noticeable

that women have a reduced social support network.

·

The couple in symmetric transition: the traditional couple began to

falter in the mid-20th century due to the crisis of positivism (Kuhn, 1962),

along with the advances of feminism and the recognition of gender diversity

(Bernard, 1972; Marshall, 2018; Rodríguez-Pizarro and Rivera-Crespo, 2020). In

some communities they fail to adapt to the changes (Medina, et al. 2013), men

remain peripheral to parenting and household responsibilities while maintaining

their traditional role. On the other hand, women gain empowerment by having

university studies, a well-paid job and a considerable external support network

beyond the family, although they continue to perform the role of carers within the household. They discredit each other in

the presence of third parties, and include them in fights. These couples

continue to be governed by the patriarchal cultural imaginary (Medina, 2022a).

·

The symmetric supportive post-traditional couple: This one recognises gender equality and the diversity of types of

couples (Ariza, et al., 2021; Arreola, 2021; Bravo and Sanchez 2022; Sabbagh

and Golden, 2021; García, 2020; Qian, and Hu, 2021; Scheinkman,

2019),). Research reports a different narrative of what a woman and a man

should be (Butler, 2020), as well as new masculinities (Endara, 2018). They are

post-romantic couples; the relationship is constituted from confluent love;

they do not see themselves together for life nor do they refer to the other as

the only one, but rather love is expanded in relational co-responsibility

(Giddens, 2008). Beck-Gernsheim (2003), Beck and

Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2001) point out that this style

of partnership empowers autonomy and personal projects, while still paying

special emotional attention to each other's needs. They recognise

and encourage each other's friendships, their socio-emotional and work spaces,

and even consider them as a stabiliser for the couple

itself.

·

The fragile complementary post-traditional couple. Its main feature is

that giving more power to the personal project than to supportiveness could

dissolve the couple in a short time. They are highly volatile couples,

constantly changing agreements, but have little tolerance for dissent. They are

distinguished by the fact that one of them, with a certain narcissistic

profile, dominates the relationship in fundamental aspects such as residence,

having or not having children, time, etc. And he/she is intolerant of

criticism. Both are financially autonomous and have a wide network of friends,

so the bond quickly unravels in the face of any dissent. It is related to

Bauman's (2003) idea of liquid love, which is based on an ephemeral fragile

bond (Benavides, et al. 2021).

METHOD

Design

The present study has an instrumental design, as it focuses on examining the psychometric properties of a measurement instrument (Ato et al., 2013).

Participants

A quota and convenience type of sampling were used. The selection criteria were that the person surveyed is in a formal or informal relationship, that is dating, married, living together or not, regardless of the gender and length of the relationship. This application was carried out by students and teachers from Centro Universitario de la Ciénega, University of Guadalajara and from Instituto Tzapopan (Jalisco, Mexico). For the pre-test phase, 61 people resident in Mexico participated: 88.1% resident in the state of Jalisco, mainly Guadalajara and Zapopan, and 11.1% in other states in the country. The sample is comprised by 44.4% men and 49.2% women, with ages ranging from 20 to 71, (M=38.5; DT=11.2). Of these, 36.5% were, at the time of carrying out the questionnaire, in an engagement relationship, 44.4% were married, and 15.9% cohabited as a couple. For the final evaluation, 1291 people resident in the states of Jalisco and Michoacán, Mexico, were contacted. The final sample is comprised of 1149 people. 71.5% identify with the female gender, 28% with male, and 0.5% did not indicate their gender, with ages ranging from 13 to 73 (M=30.08; DT=10.6). The general characteristics of the sample can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Gender, situation, duration

of the relationship and occupational situation of the sample.

|

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Gender |

||

|

Female |

821 |

71.5% |

|

Male |

322 |

28.0% |

|

Others |

6 |

0.5% |

|

Relationship situation |

|

|

|

Engagement |

555 |

48.3% |

|

Married |

414 |

36.0% |

|

Cohabiting as a couple |

180 |

15.7% |

|

Duration of the relationship |

||

|

1 to 6 months |

171 |

14.9% |

|

6 months to 1 year |

113 |

9.8% |

|

1 to 3 years |

240 |

20.9% |

|

3 to 5 years |

197 |

17.1% |

|

5 to 10 years |

187 |

16.3% |

|

10 years or more |

241 |

21.0% |

|

Occupational situation |

||

|

Unemployed |

44 |

3.8% |

|

Pensioner or retired |

13 |

1.1% |

|

Student |

307 |

26.7% |

|

Working at home with or without children |

86 |

7.5% |

|

Employee |

664 |

57.8% |

|

Others |

35 |

3.0% |

According to Arifin (2024), for the test characteristics and to achieve adequate fit indices with at least an 80% statistical power, it would be necessary to have a minimum of 378 subjects to conduct only the CFA, therefore, this condition is met.

Instruments

The Multidimensional

Couple.

The Multidimensional Couple is a test comprising a total of 40 items, divided

into 8 scales, which make up two parts.

Part 1, called Couple analysis. It starts

with a table that the person must fill in with qualitative information, where

they place the names of 5 people, the type of relationship they have with them

and the location where the relationship usually takes place. The first person

must be the partner, the other four individuals from the subject's close

circle.

Later, the 7 first scales must be filled in.

These refer to the different emotional, cognitive, physical interest, support

and protection, respect, trust and power dimensions. Each scale was initially

comprised of 8 items, in order to choose among the most adequate. They all have

a Likert-style response format of five points, with the options: 1 never, 2

almost never, 3 sometimes, 4 almost always, 5 always. The response must be

applied both to the partner and for each one of the people chosen, writing the

number corresponding to the answer under each column, forming a 5x5 matrix (4x5

in the case of the power dimension).

Part 2. The second part is formed by the

eighth scale, called Classification of the couple. It is answered only taking

into account the couple, formed by 12 items with a Likert-style response option

of five points, similar to the above (from1 never, to 5 always).

In the 8 scales there is an additional row

and column in which to add the total of the scores for each item and each

person, with which to obtain the total for each dimension and each person. With

this we obtain the mean response in each dimension and each person in the 7

dimensions of part 1. With the couple Classification scale, a sum of the total

is carried out.

Survey with socio-economic

questions.

A series of survey-type questions were asked relating to the sociodemographic

and occupational data of the people surveyed, as well as to their sentimental

situation. These were obtained from the survey models carried out for

statistical and census studies of the National Statistics and Geography

Institute (INEGI) of Mexico. They are asked what gender they identify with,

their age, city and country of residence, occupational situation, housing

conditions, type of relationship with their partner, the duration of the relationship

up until the moment of responding to the survey.

Procedure

The people who decided to participate in the study received access to

the test via an online platform. The test was self-administered, filled in on

the same platform. First, they were informed in writing about the objectives of

the research, about the application of the Law on Personal Data Protection,

informed consent and the purposes which the information received will be used

for. Once that information was provided, individuals signed the informed

consent, indicating that they were participating in the study voluntarily.

Next, they were given the instructions to respond to each one of the blocks of

the questionnaire. This work follows the recommendations established by the

Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association regarding research

involving human subjects. Likewise, it was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Department of Psychology of the University of Oviedo (Spain) and the Ethics

Committee of the University of Guadalajara (Mexico).

Data analysis

A random division of the sample into two halves has been carried out,

performing the EFA with the first half and the CFA with the second. First, an

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was carried out of the data using Kaiser's K1

criterion, as well as the scree plot, with all the items, forcing the

extraction of 7 factors. In order to test the adequacy of the data matrix that

enabled carrying out the EFA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Test for sampling

adequacy was studied, as well as Bartlett's test of sphericity. The Principal

Axis Factorization method was used for parameter estimation, robust against

univariate and multivariate violation of the variables analysed,

as well as the direct Oblimin rotation method.

Next, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out with those

same scales by means of Structural Equation Modelling. The DWLS method was

used, suitable for samples larger than 200 subjects (Martínez-Mesa et al.,

2016) and the fit of the models was checked with the RMSEA (Root Mean Square

Error of Approximation), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), CFI (Comparative Fix Index)

and SMRM (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) tests. A second order

Confirmatory Factor Analysis was also carried out with all the items, both for

the answers corresponding to the couple and to those corresponding to one of

the other people, to see if they worked as a one-dimensional test to obtain a

global score. The following values of the indexes used have been taken as a

reference of goodness of fit of the models: RMSEA≤.10, TLI>.95 and CFI≥.95

(Schreiber et al., 2006).

Throughout this process, the items that finally comprised each scale

were fine-tuned, discarding those that did not allow a good fit of the model.

Initially, the scales had a total of 8 items, and they were reduced to 5 in all

of them, except in one where there were 4 items. Once these steps were

completed, the reliability of each one of the scales was studied individually,

and globally by means of calculating McDonald’s Omega index and Cronbach's

alpha coefficient. Finally, an invariance test was performed between the male

and female groups to determine the appropriateness of the instrument to gender

and to test the internal validity of the instrument. The configural, metric,

scalar and strict models were compared in the Multidimensional Scale (for the

partner and for other people) and in the Classification of the couple scale.

The criterion to conclude that there is invariance between the groups is that

the change in the goodness of fit indices between models (CFI, TLI and SRMR) is

Δ ≤.01 and in the RMSEA Δ ≤.015. The software used to carry out the analyses

was IBM SPSS version 25 for the EFA and JASP version 0.18.3 for the CFA.

Ethics Aspects

This study was part of a larger research project “Suitability, Clinical

Utility and Acceptability of an Online Transdiagnostic Intervention for

Emotional Disorders and Stress-related Disorders in Mexican Sample: A

Randomized Clinical Trial” which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Faculty of Higher Studies Iztacala UNAM (CE/FESI/

082020/1363). All participants read and agreed to an electronic consent before

completing the self-report questionnaires online.

RESULTS

Exploratory Factor

Analysis

Table 2 contains the

descriptive analysis of the items from the 7 dimensions for the answers given

with respect to the partner, and the Couple Classification scale. The

correlation indexes of each one with its dimension are also added, and the

weight in the factor. The asymmetry and kurtosis indicate that the items do not

meet the assumption of normality. Thus, Table 3 shows the results of the EFA.

The KMO test and Bartlett's sphericity test indicate a good fit of the 8

scales, with reliability indexes above .84 and positive correlation among all

of them. For the scale of the 39 items, the goodness of fit assumptions is met

again, and the general reliability is .97.

Table 2. Averages, typical

deviations, asymmetry indexes and kurtosis, corrected item-test correlation and

factor weights of each item in their factor.

|

|

Partner |

Other people |

||||||||||

|

Item |

M |

SD |

g1 |

g2 |

rit |

λ |

M |

SD |

g1 |

g2 |

rit |

λ |

|

EMO1. They accept you as you are without trying

to change you |

4.20 |

0.99 |

-1.35 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

0.64 |

4.43 |

1.00 |

-2.16 |

4.33 |

0.29 |

0.45 |

|

EMO2. You feel comfortable in their presence |

4.60 |

0.71 |

-2.19 |

5.89 |

0.74 |

0.85 |

4.64 |

0.66 |

-2.48 |

8.23 |

0.55 |

0.74 |

|

EMO3. You feel loved thanks to their kind

gestures |

4.52 |

0.84 |

-1.86 |

3.08 |

0.69 |

0.81 |

4.28 |

0.98 |

-1.33 |

1.17 |

0.47 |

0.69 |

|

EMO4. Their presence makes you happy |

4.64 |

0.65 |

-2.10 |

5.00 |

0.77 |

0.88 |

4.60 |

0.68 |

-1.77 |

3.08 |

0.65 |

0.84 |

|

EMO5. I have fun with them |

4.48 |

0.79 |

-1.57 |

2.35 |

0.74 |

0.86 |

4.54 |

0.69 |

-1.62 |

2.81 |

0.60 |

0.81 |

|

COG1. They acknowledge that one can have

different preferences to theirs |

4.14 |

1.00 |

-1.06 |

0.58 |

0.36 |

0.49 |

4.22 |

0.97 |

-1.26 |

1.18 |

0.36 |

0.50 |

|

COG2. They celebrate your small achievements |

4.52 |

0.88 |

-2.05 |

3.80 |

0.74 |

0.86 |

4.32 |

0.93 |

-1.34 |

1.28 |

0.70 |

0.84 |

|

COG3. They support you when you fail |

4.60 |

0.82 |

-2.32 |

5.19 |

0.76 |

0.88 |

4.36 |

0.90 |

-1.34 |

1.23 |

0.70 |

0.84 |

|

COG4. They make me feel important |

4.44 |

0.87 |

-1.67 |

2.47 |

0.75 |

0.86 |

4.25 |

0.89 |

-1.02 |

0.47 |

0.67 |

0.81 |

|

COG5. They motivate me to continue despite

failures or problems |

4.60 |

0.80 |

-2.39 |

5.89 |

0.74 |

0.86 |

4.49 |

0.80 |

-1.69 |

2.62 |

0.70 |

0.84 |

|

PI1. They make positive comments about your

appearance |

4.15 |

1.04 |

-1.11 |

0.50 |

0.80 |

0.88 |

3.43 |

1.28 |

-0.37 |

-0.83 |

0.69 |

0.81 |

|

PI2. I like their hugs |

4.77 |

0.65 |

-3.39 |

12.40 |

0.49 |

0.62 |

3.83 |

1.44 |

-0.90 |

-0.60 |

0.51 |

0.65 |

|

PI3. They try to be attractive to you |

4.35 |

0.96 |

-1.49 |

1.56 |

0.86 |

0.92 |

3.09 |

1.44 |

-0.13 |

-1.24 |

0.80 |

0.89 |

|

PI4. Their constant comments make me feel very

happy |

4.12 |

1.06 |

-1.03 |

0.25 |

0.81 |

0.88 |

3.09 |

1.37 |

-0.15 |

-1.13 |

0.76 |

0.86 |

|

PI5. They make me feel good-looking |

4.21 |

1.06 |

-1.27 |

0.91 |

0.83 |

0.90 |

2.88 |

1.47 |

0.04 |

-1.35 |

0.75 |

0.86 |

|

PRO1. You feel safe with them |

4.56 |

0.82 |

-2.12 |

4.36 |

0.77 |

0.86 |

4.15 |

1.05 |

-1.20 |

0.81 |

0.74 |

0.84 |

|

PRO2. They take into account your needs |

4.27 |

0.94 |

-1.24 |

0.96 |

0.78 |

0.86 |

3.77 |

1.10 |

-0.64 |

-0.23 |

0.73 |

0.83 |

|

PRO3. They make sure nothing bad happens to you |

4.64 |

0.74 |

-2.29 |

5.24 |

0.73 |

0.83 |

4.11 |

1.06 |

-1.04 |

0.34 |

0.75 |

0.85 |

|

PRO4. Their comments make me feel calm |

4.26 |

0.92 |

-1.14 |

0.72 |

0.77 |

0.85 |

4.13 |

0.94 |

-1.05 |

0.84 |

0.73 |

0.83 |

|

PRO5. They are available for me in situations of

distress |

4.43 |

0.89 |

-1.72 |

2.63 |

0.79 |

0.87 |

4.07 |

1.03 |

-1.01 |

0.51 |

0.71 |

0.82 |

|

RES1. They listen carefully to your opinions

without becoming agitated when they are different to theirs |

4.01 |

1.02 |

-0.89 |

0.22 |

0.71 |

0.83 |

4.13 |

0.92 |

-0.93 |

0.39 |

0.65 |

0.79 |

|

RES2. Even though they have different points of

view to mine about a situation in particular, we talk, discuss and negotiate

in order to reach a satisfactory consensus for both of us |

4.18 |

1.00 |

-1.20 |

0.93 |

0.74 |

0.85 |

4.11 |

0.97 |

-1.08 |

0.84 |

0.68 |

0.81 |

|

RES3. They respect your decisions even if they

disagree |

4.18 |

0.96 |

-1.06 |

0.54 |

0.72 |

0.83 |

4.21 |

0.95 |

-1.19 |

1.05 |

0.68 |

0.81 |

|

RES4. They avoid doing things they know bother me |

3.74 |

1.03 |

-0.69 |

0.19 |

0.66 |

0.79 |

3.85 |

1.00 |

-0.68 |

0.08 |

0.61 |

0.75 |

|

RES5. They avoid comparing me in front of and

with other people |

4.34 |

1.06 |

-1.74 |

2.38 |

0.54 |

0.68 |

4.31 |

1.02 |

-1.63 |

2.21 |

0.57 |

0.71 |

|

TRU1. They support me financially if I need it |

4.65 |

0.78 |

-2.52 |

6.20 |

0.56 |

0.70 |

4.02 |

1.17 |

-1.05 |

0.25 |

0.46 |

0.63 |

|

TRU2. I am not afraid to show vulnerability when

there is a problem |

4.36 |

1.01 |

-1.60 |

1.84 |

0.64 |

0.77 |

4.20 |

1.08 |

-1.30 |

0.90 |

0.62 |

0.77 |

|

TRU3. I am not afraid to tell them secrets,

personal and intimate things |

4.40 |

0.97 |

-1.71 |

2.36 |

0.71 |

0.83 |

4.24 |

1.07 |

-1.39 |

1.19 |

0.61 |

0.78 |

|

TRU4. They always believe in me |

4.51 |

0.86 |

-1.95 |

3.56 |

0.73 |

0.84 |

4.50 |

0.77 |

-1.64 |

2.51 |

0.66 |

0.80 |

|

TRU5. They are discreet with things I confide in

them |

4.63 |

0.75 |

-2.40 |

6.01 |

0.61 |

0.75 |

4.46 |

0.85 |

-1.77 |

3.11 |

0.56 |

0.73 |

|

POW1. They express admiration for me |

4.31 |

0.94 |

-1.36 |

1.34 |

0.71 |

0.85 |

4.06 |

0.96 |

-0.82 |

0.17 |

0.63 |

0.81 |

|

POW2. They like my personal style (clothes,

hairstyle, etc.) |

4.32 |

0.87 |

-1.22 |

1.11 |

0.67 |

0.82 |

4.04 |

0.95 |

-0.73 |

0.03 |

0.60 |

0.80 |

|

POW3. They take my opinions into account |

4.28 |

0.89 |

-1.20 |

1.09 |

0.72 |

0.85 |

3.93 |

0.96 |

-0.53 |

-0.32 |

0.57 |

0.77 |

|

POW4. They respect my personal space and time |

4.34 |

0.95 |

-1.48 |

1.71 |

0.58 |

0.75 |

4.61 |

0.74 |

-2.19 |

5.16 |

0.44 |

0.65 |

|

CLAS1. Your partner accepts displays of affection

towards you from your friends |

4.02 |

1.07 |

-1.06 |

0.56 |

0.74 |

0.79 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS2. Your partner considers the support you

receive from your friends to be important |

4.19 |

1.05 |

-1.24 |

0.78 |

0.81 |

0.86 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS3. Your partner accepts that your friends

express how attractive you are |

3.81 |

1.24 |

-0.82 |

-0.32 |

0.74 |

0.80 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS4. Your partner accepts the time you spend

with your friends |

4.10 |

1.13 |

-1.15 |

0.43 |

0.84 |

0.88 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS5. Your partner values the advice your

friends give you |

3.90 |

1.07 |

-0.75 |

-0.10 |

0.74 |

0.79 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS6. Your partner likes it when your friends

admire you |

4.03 |

1.17 |

-1.08 |

0.23 |

0.78 |

0.83 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS7. Your partner accepts without difficulty

that you go out alone to have fun with your friends |

3.91 |

1.25 |

-0.92 |

-0.26 |

0.78 |

0.83 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS8. Your partner is glad that you have friends

beyond your family and your partner |

4.08 |

1.15 |

-1.10 |

0.20 |

0.83 |

0.87 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS9. Your partner knows the significant people

and the type of relationship you have with them |

4.38 |

1.00 |

-1.65 |

1.94 |

0.63 |

0.69 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLAS10. Your partner considers that your

professional project is a strength for your shared project |

4.50 |

0.94 |

-2.02 |

3.47 |

0.55 |

0.61 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Note. M= Mean; SD= Standard

deviation; EMO= Emotion; COG= Cognitive; PI= Physical interest; PRO= Support

and Protection; RES=Respect; TRU= Trust; POW=Power; CLAS= Classification of the

couple. g1 = Skewness; g2 = Kurtosis; rit

= item-test correlation; λ = Rotated factor loading.

Table 3. KMO and Bartlett goodness

of fit tests, reliability index, mean, standard deviation and correlation

between the dimensions.

|

Factor |

α |

ω |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

M |

SD |

|

|

Partner |

Total scales

1-7 (a) |

0.97 |

0.97 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.Emotional |

0.85 |

0.85 |

.757** |

.725** |

.763** |

.724** |

.713** |

.738** |

.490** |

22.46 |

3.22 |

|

|

2. Cognitive |

0.84 |

0.85 |

.713** |

.821** |

.781** |

.764** |

.780** |

.559** |

22.33 |

7.48 |

||

|

3.Physical interest |

0.90 |

0.92 |

.756** |

.675** |

.685** |

.779** |

.434** |

21.62 |

4.13 |

|||

|

4.Protection |

0.91 |

0.91 |

.798** |

.760** |

.800** |

.508** |

2.18 |

3.75 |

||||

|

5.Respect |

0.85 |

0.85 |

.751** |

.783** |

.617** |

22.57 |

3.46 |

|||||

|

6.Trust |

0.84 |

0.85 |

.814** |

.599** |

20.47 |

4.06 |

||||||

|

7.Power |

0.84 |

0.84 |

.625** |

17.27 |

3.01 |

|||||||

|

|

8.Classification of the couple (b) |

0.93 |

0.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40.97 |

8.94 |

|

Other people |

Total scales

1-7 (c) |

0.95 |

0.95 |

|

|

|||||||

|

1.Emotional |

0.72 |

0.73 |

.649** |

.411** |

.568** |

.549** |

.557** |

.549** |

.274** |

22.51 |

2.83 |

|

|

2. Cognitive |

0.82 |

0.83 |

.499** |

.695** |

.643** |

.650** |

.653** |

.301** |

21.67 |

3.47 |

||

|

3.Physical interest |

0.87 |

0.88 |

.593** |

.480** |

.433** |

.548** |

.151** |

16.34 |

5.73 |

|||

|

4.Protection |

0.89 |

0.89 |

.707** |

.642** |

.694** |

.238** |

20.30 |

4.34 |

||||

|

5.Respect |

0.83 |

0.83 |

.687** |

.706** |

.280** |

21.44 |

3.72 |

|||||

|

6.Trust |

0.79 |

0.79 |

.672** |

.279** |

20.63 |

3.82 |

||||||

|

|

7.Power |

0.76 |

0.77 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.313** |

16.65 |

2.79 |

Note. α= Cronbach’s

Alpha Index; M= Mean; SD= Standard Deviation; *p= ˂.001. (a) KMO=0.98; (b) KMO=0.94; (c) KMO=0.96.

Tables 2 and 3 show the same

results for the answers offered to people other than the partner, taking as a

reference the one chosen as "person 1". Again, the assumption of

normality is not met, the goodness of fit indexes confirms the fit of the

analysis, the reliability indexes are adequate, above 0.72, and there is a

positive correlation between all the scales, including here also the

Classification of the Couple.

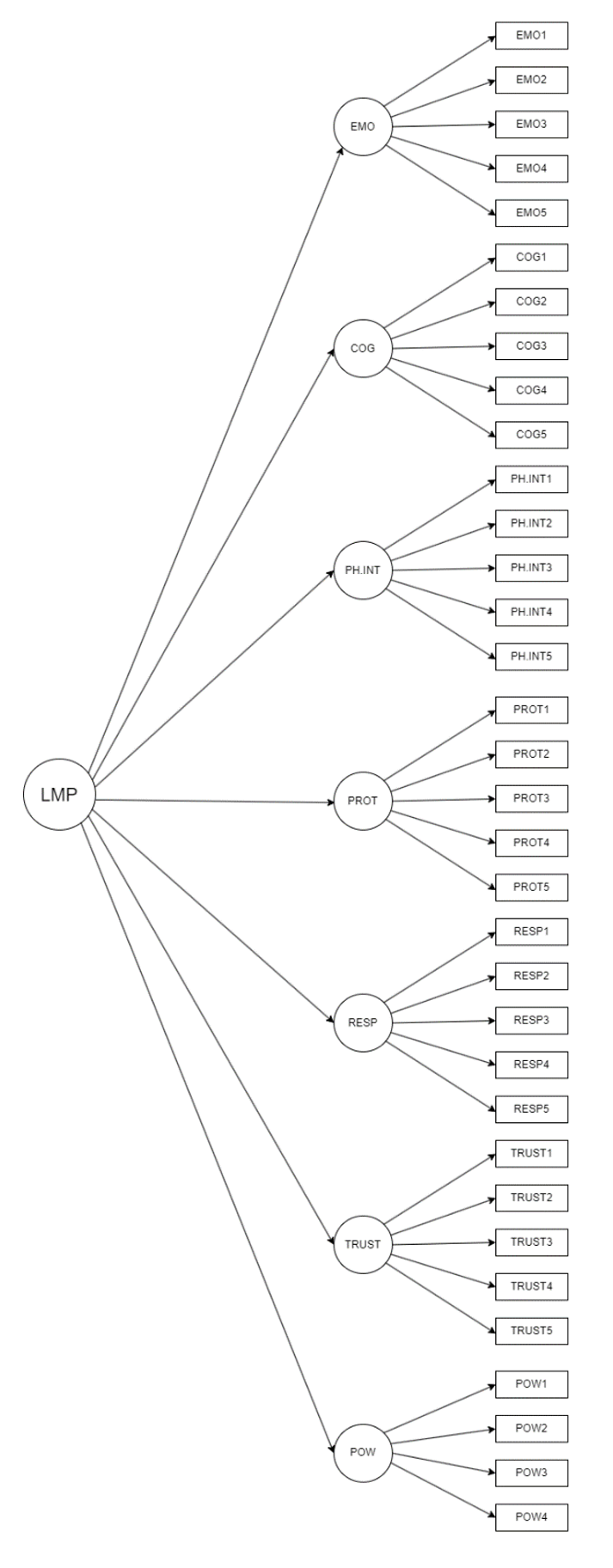

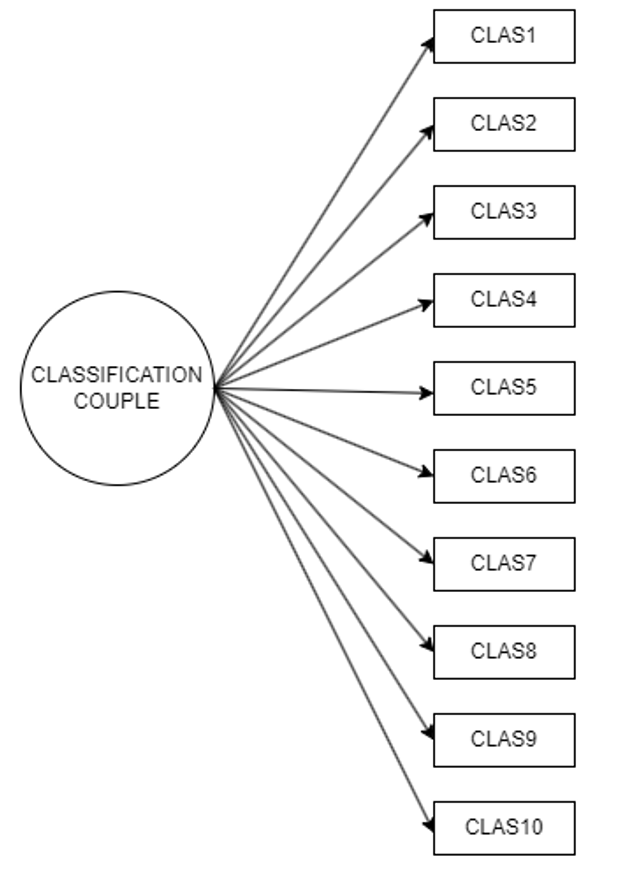

Confirmatory Factor

Analysis

The results of the

confirmatory factor analysis for the scales in the measurement of the partner

and the people who are not the partner can be observed in Table 4. Adequate fit

indices are observed for the seven-factor model and for the model with a second-order

latent factor, in which the Classification of the couple scale is not included.

This allows us to obtain a total scale score of the seven dimensions with a

higher explanatory level. Figures 1 to 2 show the diagram of the CFA for the

main scale for the partner and other people, and the classification of the

couple scale, respectively. The factor loadings for each scale are shown in

Table 5.

Table 4. Goodness-of-Fit Indices of

the models for the partner and for the people other than the partner

|

|

Partner |

Other people |

||||||

|

|

TLI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

TLI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

|

Seven-Factor model |

1 |

1 |

0.038 |

0.04 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.048 |

0.05 |

|

Seven-Factor with

second-order latent factor |

1 |

1 |

0.042 |

0.04 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.052 |

0.06 |

|

Classification of the couple |

1 |

1 |

0.063 |

0.04 |

|

|

|

|

Note. CFI = comparative fit

index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index. RMSEA = root mean square error of

approximation. SRMR = standardized root mean square

Table 5. Factorial loads standardized for second-order

model and Classification of the couple scale.

|

|

Factor |

Item |

λ Partner |

λ Other People |

|

First order

factors |

Emotional |

EMO1 |

0.296 |

0.299 |

|

EMO2 |

0.373 |

0.442 |

||

|

EMO3 |

0.384 |

0.486 |

||

|

EMO4 |

0.385 |

0.505 |

||

|

|

EMO5 |

0.384 |

0.472 |

|

|

Cognitive |

COG1 |

0.152 |

0.248 |

|

|

COG2 |

0.237 |

0.373 |

||

|

COG3 |

0.247 |

0.372 |

||

|

COG4 |

0.254 |

0.385 |

||

|

|

COG5 |

0.251 |

0.392 |

|

|

Physical Interest |

PI1 |

0.403 |

0.613 |

|

|

PI2 |

0.389 |

0.576 |

||

|

PI3 |

0.436 |

0.638 |

||

|

PI4 |

0.427 |

0.632 |

||

|

|

PI5 |

0.424 |

0.636 |

|

|

Support and Protection |

PRO1 |

0.242 |

0.337 |

|

|

PRO2 |

0.246 |

0.331 |

||

|

PRO3 |

0.238 |

0.336 |

||

|

PRO4 |

0.250 |

0.347 |

||

|

|

PRO5 |

0.237 |

0.331 |

|

|

Respect |

RES1 |

0.314 |

0.415 |

|

|

RES2 |

0.320 |

0.434 |

||

|

RES3 |

0.302 |

0.423 |

||

|

RES4 |

0.290 |

0.381 |

||

|

|

RES5 |

0.262 |

0.376 |

|

|

Trust |

TRU1 |

0.234 |

0.239 |

|

|

TRU2 |

0.247 |

0.270 |

||

|

TRU3 |

0.266 |

0.275 |

||

|

TRU4 |

0.294 |

0.325 |

||

|

|

TRU5 |

0.252 |

0.272 |

|

|

Power |

POW1 |

0.129 |

0.260 |

|

|

POW2 |

0.115 |

0.239 |

||

|

POW3 |

0.129 |

0.248 |

||

|

|

|

POW4 |

0.115 |

0.236 |

|

Second Order Factor |

Emotional |

0.910 |

0.810 |

|

|

Cognitive |

0.960 |

0.890 |

||

|

Physical Interest |

0.890 |

0.680 |

||

|

Support and Protection |

0.960 |

0.920 |

||

|

Respect |

0.930 |

0.850 |

||

|

Trust |

0.950 |

0.930 |

||

|

|

|

Power |

0.990 |

0.940 |

|

Classification of the couple |

CLAS1 |

0.820 |

- |

|

|

CLAS2 |

0.890 |

- |

||

|

CLAS3 |

0.834 |

- |

||

|

CLAS4 |

0.915 |

- |

||

|

CLAS5 |

0.818 |

- |

||

|

CLAS6 |

0.851 |

- |

||

|

CLAS7 |

0.878 |

- |

||

|

CLAS8 |

0.918 |

- |

||

|

CLAS9 |

0.743 |

- |

||

|

|

|

CLAS10 |

0.677 |

- |

Notes. All values were

significant (p<0.05). λ = Factorial loads

standardized

Figure 1. CFA of the

Emotional dimension for the partner and for other people.

Figure 2. CFA of the

Cognitive dimension for the partner and for other people.

Invariance analysis

The factorial invariance

analysis, shown in Table 6, indicates that the scale performs similarly in men

and women, both for the main scale and for the Classification of the couple

scale. This means that comparisons can be made between men and women with both

scales for both partners and other people.

Table 6. Metric invariance of

multigroup comparisons by sex.

|

Partner |

Other people |

|||||||

|

|

TLI (∆TLI) |

CFI (∆CFI) |

RMSEA (∆RMSEA) |

SRMR(∆SRMR) |

TLI (∆TLI) |

CFI (∆CFI) |

RMSEA (∆RMSEA) |

SRMR(∆SRMR) |

|

Second-order model scale |

||||||||

|

Configural |

0.999 |

0.999 |

0.035 |

0.042 |

0.991 |

0.991 |

0.052 |

0.063 |

|

Metric |

0.998 (0.001) |

0.998 (0.001) |

0.043 (0.008) |

0.047 (0.000) |

0.990 (0.001) |

0.990 (0.001) |

0.054 (0.002) |

0.065 (0.002) |

|

Scalar |

0.999 (0.001) |

0.998 (0.000) |

0.035 (0.008) |

0.044 (0.003) |

0.991 (0.000) |

0.991 (0.001) |

0.050 (0.004) |

0.063 (0.002) |

|

Strict |

0.999 (0.000) |

0.998 (0.000) |

0.035 (0.000) |

0.044 (0.001) |

0.991 (0.000) |

0.991(0.000) |

0.050 (0.000) |

0.063 (0.000) |

|

Classification of the couple scale |

||||||||

|

Configural |

0.997 |

0.998 |

0.062 |

0.039 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Metric |

0.997 (0.000) |

0.998 (0.000) |

0.063 (0.001) |

0.043 (0.004) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Scalar |

0.998 (0.001) |

0.998 (0.000) |

0.054 (0.009) |

0.040 (0.001) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Strict |

0.998 (0.000) |

0.998 (0.000) |

0.054 (0.000) |

0.040 (0.001) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Note. CFI = comparative fit

index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index. RMSEA = root mean square error of

approximation. SRMR = standardized root mean square. ∆= Increase in the index

between models.

Validity of the instrument

The goodness of fit indexes

of the models are adequate for all the scales. Likewise, a positive and

significant correlation is observed between all the scales, for the dimensions

of the couple and of the other people, among each other and with the Couple

Classification scale, as can be seen in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The analysis of the seven dimensions between the partner and up to four

people with whom one is intimate shows that the socio-emotional burden is

distributed among all of them. Therefore, the partner is not the only and

exclusive factor of intimacy and emotional and social well-being, refuting the

unidimensional couple, to give way to the multidimensional one (Caillé, 1992, Sluzki, 2010, Speck

and Attneave, 1973, Antonucci, et al., 2001).

This new landscape of multiple dimensions of the couple is linked to the

current material and cultural conditions of individuals, especially women,

which have expanded affections beyond the heterosexual couple (Yela, 2000;

Stange et al., 2017; Beck- Gernsheim, 2003; Minuchin

and Nichols, 2010, Tamarit, et al., 2021).

The instrument could test the hypothesis that mutual recognition of the

personal socio-emotional network beyond the family is a positive resource for

emotional support and well-being in some types of couples (Graham, 2000,

Kaufman and Taniguchi, 2006, Reina, 2020), which we will call post-traditional.

On the other hand, in traditional couples such support networks are smaller and

become a source of relational tension. That is, the external network

intensifies the control and abuse of the partner (Plazaola-Castaño

et al., 2008; Estrada et al., 2012; Alencar and Cantera, 2017;

Rodríguez-Fernández and Ortiz-Aguilar, 2018).

The instrument shows that there is a positive relationship between the

different dimensions when the information refers to people in their immediate

surroundings and the couple itself. The more the couple’s external intimate

network is nourished, the better nourished it is (relationally). In other

words, people who take more care of these areas also score higher in the Couple

Typification, being able to build one of a post-traditional type, with the

benefits that this entails (Watzlawick, et al., 1985; Minuchin and Nichols,

2010; Endara, 2018).

On the other hand, the multidimensional couple is a support network for

the couple itself, or the person, to face multiple daily problems,

strengthening resilience, identity well-being and the health of people (Cyrulnik, 2016, Han et al., 2019) This disrupts

individuality, to redefine it as a person who is constituted and evolves from

the significant network. Particularly for couples, the recognition of the

non-familial socio-emotional support network has an impact on the person's

awareness and self, empowering them and giving them the freedom to decide with

whom to share their life as a couple (Medina et al., 2018).

Given these findings, the instrument allows us to recognise

a second (Watzlawick et al., 1976) and third (McDowell et al., 2019, Medina,

2022a, Medina, 2022b) order systemic multidimensional complexity in the couple.

Second order, because the awareness of the intimate network implies a

new view of each other and a meta-learning that can contribute to rethinking

rules and agreements for change in the relationship. In other words, the

impacts of the intimate network translate into self-critical reflections that

enable the couple to evolve and, paradoxically, feel conjugal satisfaction.

Regarding the third order, an awareness of the importance of the intimate

network in conjugal well-being demystifies patriarchal and romantic dogmas, in

particular by broadening the critical view of the multidimensionality of

emotional exclusivity.

Limitations and strengths

The instrument can become a resource for psychosocial research to

correlational more variables depending on the objective being sought. For

example, among gender-diverse couples, couples without children or with

children, couples with minor children and older children. Between, boyfriends

or married couples, whether they live together or not, those who have been

together longer than those who are starting, those who come from a divorce or

not, or because of their status or social classes, etc. Regarding the

classification of couples, work could be done to include other types of couples

and expand the range of indicators and questions in order to have greater

empirical certainty in the classification of couples.

Clinical implications

This instrument is a great resource for a couple of psychotherapy, it

could be applied before the clinical process, yielding a series of indicators

and topics that will raise awareness of deficiencies in some socio-emotional

dimensions. On the other hand, typification could be of great help in

recognizing the symbolism and relational patterns linked to the reason for

consultation. In other words, the symptom or problem that brought the couple to

therapy can be connected with an inter-systemic contextualization, which will

facilitate working on structural changes of the second and third order: roles,

hierarchy, rules, mythologies, and injustices.

Conclusion

With this, it is concluded that the multidimensional couple is the

socio-emotional network of choice - including the non-familial partner - that

provides solidarity, understanding, affective support, recognition, feeling

valued, trust, support, admiration, respect and safety (Caillé,

1992, Sluzki, 2010, Speck and Attneave,

1973, Denborough, 2008, Medina 2022).

ORCID

Raúl

Medina Centeno: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9277-5561

Sara

Menéndez-Espina: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4238-4693

José

Antonio Llosa: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2644-020X

Esteban

Agulló-Tomás: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3549-2928

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Raúl Medina Centeno:

Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Original Draft, Supervision, Management

and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and

execution, Writing - Review & Editing.

Sara Menéndez-Espina: Methodology,

Formal análisis, Visualization, Writing - Original

Draft.

José Antonio Llosa:

Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft.

Esteban Agulló-Tomás: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft,

Writing - Review & Editing.

FUNDING

SOURCE

This study did not receive funding.

CONFLICT OF

INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Readers may request the data from the corresponding author.

REVIEW

PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external peers in double-blind mode.

The editor in charge was Renzo Rivera. The review process is included as supplementary material 1.

DATA

AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Abad, F., Díaz, J., Gil, V., y García, C. (2011). Medición

en ciencias sociales y de la salud. [Measurement in health and social sciences]. Síntesis.

Alencar, R. y Cantera, L. (2017). Violencia en la pareja: el rol de la red social [Intimate partner violence: the role of the social network].

Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicología, 69(1),

90-106.

Antonucci, T. C., Lansford,

J. E., & Akiyama, H. (2001). Impact of positive and negative aspects of marital relationships and

friendships on well-being of older adults. Applied Developmental Science, 5(2),

68–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0502_2

Arias-Galicia, L. (2003). La Escala de Satisfacción Marital: análisis de su

confiabilidad y validez en una muestra de supervisores mexicanos [The Marital Satisfaction Scale: analysis of its reliability

and validity in a sample of Mexican supervisors].

Interamerican Journal

of Psychology, 37(1), 67-92.

Arifin, W. N. (2024). Sample size

calculator (web). Retrieved from http://wnarifin.github.io

Ariza, G., Agudelo, J., Saldarriaga, D., Vanegas, A. y

Saldarriaga L. (2021). Consecuencias jurídicas de las transformaciones en las

parejas contemporáneas en Colombia [Legal consequences

of transformations in contemporary couples in

Colombia]. En Vásquez Santamaría, J. E., y Roldán Villa, A. M. (eds..).

Debates contemporáneos en derecho de familias, de infancias y de adolescencias.

Desafíos y realidades. Fondo Editorial Universidad Católica Luis Amigó.

Arreola, R. (2021). La piel del mundo: Una mirada

del psicoanálisis relacional a las familias contemporáneas [The skin of the

world: A look from relational psychoanalysis to contemporary families]. Caligrama.

Balbo, L. (1994). La doble presencia [The double presence].

En C. Borderías, C. Carrasco, y C. Alemany (eds.), Las mujeres y el trabajo.

Rupturas conceptuales (pp. 503-5013). Icaría.

Barón, M. O. (2002). Apego y satisfacción

afectivo-sexual en la pareja [Attachment and affective-sexual satisfaction in the couple]. Psicothema, 14(2), 469-475.

Bateson, G. (1973). Steps to an Ecology

of Mind. The University of Chicago Press.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Liquid love: On the

frailty of human bonds. Polity.

Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2003). La

reinvención de la familia: En busca de nuevas formas de convivencia. [The Reinvention of the Family: In Search

of New Forms of Coexistence]. Paidós.

Beck, U. y Beck-Gernsheim,

E. (2001). El normal caos del amor: las nuevas formas de relación amorosa.

[The normal chaos of

love: the new forms of love relationship]. Paidós.

Benavides, A., Villota, M. y Laverde, D. (2021). La

democratización de los vínculos en pareja en una propuesta de investigación e

intervención sistemática. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Familia, 13(1),

89-116. https://doi.org/10.17151/rlef.2021.13.1.6

Bernard, J. (1972). The Future of

Marriage. Word Publishing.

Bravo, A. y Sánchez R. (2022). Las Premisas Históricas-socioculturales de la Pareja

en la Ciudad de México: Exploración y Análisis Cualitativo [The

Historical-Sociocultural Premises of

the Couple in Mexico City: Exploration and Qualitative Analysis]. Acta Inv. Psicol.

12(3), 71-85.

Butler, J. (2020). The Force of

Nonviolence. Penguin Random House.

Caillé, P. (1992). Uno más

uno son tres: la pareja revelada

a sí misma [One plus

one is three: the couple revealed to itself]. Grupo Planeta (GBS).

Castañeda-Renteria, L. (2016). Las distintas formas de ‘estar’ en pareja: ausencias, presencias y las maneras de estar juntos sin estarlo [The different

ways of 'being' as a couple: absences, presences and ways of being together

without being together]. Revista REDES, (33), 93-104. https://www.redesdigital.com/index.php/redes/article/view/161

Cyrulnik, B. (2016). ¿Por qué la resiliencia? [Why resiliency?]. En

B. Cyrulnik and M. Anaut (eds.)

¿Por qué la resiliencia?

Lo que nos permite

reanudar la vida. (pp. 13-28).

Gedisa.

Denborough, D. (2008). Collective narrative practice: Responding to

individuals, groups, and communities who have experienced trauma. Dulwich Centre Publications.

Díaz-Loving, R., & Armenta Hurtarte,

C. (2008). Comunicación y Satisfacción:

Analizando la Interacción

de Pareja [Communication and Satisfaction: Analyzing Couple Interaction]. Psicología Iberoamericana, 16. 23-27. https://doi.org/10.48102/pi.v16i1.294

Endara, G. (2018). ¿Qué hacemos con la(s) nuevas masculinida(des)? Reflexiones antipatriarcales

para pasar del privilegio al cuidado [What do we do with the new

masculinities? Anti-patriarchal reflections to move from privilege to care].

Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES-ILDIS).

Estrada, C., Herrero, J., & Rodríguez,

F. J. (2012). Support networks of women victims of partner violence in Jalisco

(Mexico). Universitas Psychologica, 11(2), 523-534. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy11-2.ramv

Flores-Galaz. M. (2011). Comunicación y conflicto:

¿Qué tanto impactan en la satisfacción marital? [Communication and conflict: How much do they impact

marital satisfaction?]. Acta de

investigación psicológica, 1(2), 216-232.

http://doi.org/10.22201/fpsi.20074719e.2011.2.204

García, J. (2020) La división de los roles de género

en las parejas en las que solo trabaja la mujer en Estados Unidos y España [The division of

gender roles in couples in which only the

woman works in the United States

and Spain]. Revista Española de Investigaciones

Sociológicas, 170, 73-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.170.73.

Giddens, A. (2008). La transformación de la

intimidad. Sexualidad, amor y erotismo en las sociedades modernas [The transformation of intimacy. Sexuality,

love and eroticism in modern societies]. Cátedra.

González, A. R., Bayarre, H.

y Artiles, L. (2004) Construcción de un instrumento para medir la satisfacción

personal en mujeres de mediana edad [Construction of an instrument

to measure personal satisfaction in middle-aged women]. Rev Cubana Salud Pública, 30(2).

Graham, J. (2000). Marital resilience: A

model of family resilience applied to the marital dyad. Marriage & Family: A Christian Journal, 3(4), 407-420.

Haley, J. (1980a). Terapia no convencional: las

técnicas psiquiátricas de Milton H. Erickson. [Unconventional Therapy: The Psychiatric Techniques of

Milton H. Erickson]. Amorrortu.

Han, S. H., Kim, K. & Burr, J. (2019). Friendship and Depression Among Couples in

Later Life: The Moderating Effects of Marital Quality. The Journals of

Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 74,

222-231. http://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx046

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure

of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50,

93-98. http://doi.org/10.2307/352430

Higuera, J. A. (2006). The acceptance and

commitment therapy (ACT) as a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) development.

EduPsykhé: Revista de psicología y psicopedagogía, 5(2), 287-304.

Hochschild, A. R. y Machung, A.

(1989). The Second

Shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Viking Penguin

Ibáñez, N., Linares, J. L., Vilaregut,

A., Virgili, C. y Campreciós, M. (2012). Propiedades

psicométricas del Cuestionario de Evaluación de las Relaciones Familiares

Básicas (CERFB) [Psychometric properties

of the Basic Family Relationships Assessment Questionnaire

(CERFB)]. Psicothema, 24(3), 489-494.

Iraurgi, I., Sanz, M. y Martínez-Pampliega, A. (2009).

Adaptación y estudio psicométrico de dos instrumentos de pareja: índice de

satisfacción matrimonial y escala de inestabilidad matrimonial [Adaptation and psychometric study of two

couple instruments: marital

satisfaction index and

marital instability scale].

Revista De Investigación En Psicología, 12(2), 177–192.

https://doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v12i2.3763

Jondec, N. (2020). Terapia sistémica en pareja con

problemas comunicacionales [Systemic therapy for couples

with communication problems]. Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal.

Kaufman, G. y Taniguchi, H.

(2006). Gender and

Marital Happiness in Later Life. Journal of Family issues. 27(6),

735-757. http://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05285293

Kuhn, T. (1962). The Structure of

Scientific Revolutions. University Chicago Press.

Larson, M. y Bahr, H. (1980). The

Dimensionality of Marital Role Satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the

Family, 42(1), 45-55. http://doi.org/10.2307/351932

Lauer, R., Lauer, J. y Kerr, S. (1990).

The long-term marriage: Perceptions of stability and satisfaction. The

International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 31(3), 189-195.

http://doi.org/10.2190/H4X7-9DVX-W2N1-D3BF

Linares, J. (1996). Identidad y narrativa: La

terapia familiar en la práctica clínica [Identity

and narrative: Family therapy

in clinical practice]. Paidós.

Linares, J. (2010). Paseo por el amor y el odio: la

conyugalidad desde una perspectiva evolutiva [Walk through love and hate: conjugality from an evolutionary

perspective]. Revista Argentina de Clínica

Psicológica, 19(1), 75-81.

Linares, J. (2012). Terapia familiar ultramoderna.

La inteligencia terapéutica [Ultramodern family therapy. Therapeutic intelligence]. Herder.

Locke, H. y Wallace, K. (1959). Short

marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage

and family living, 21(3), 251-255. http://doi.org/10.2307/348022

Marcuse, H. (1964). One dimensional man.

Beacon Press.

Marshall, P. (2018). Matrimonio entre personas del

mismo sexo: una aproximación desde la política del reconocimiento [Same-sex marriage: an approach from

the politics of recognition] Polis. Revista

Latinoamericana, 17(49), 201-230.

https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682018000100201

Martínez-Mesa, J., González-Chica, D. A., Duquia, R. P., Bonamigo, R. R.,

& Bastos, J. L. (2016). Sampling: how to select participants in my research study?.

Anais brasileiros de dermatologia,

91, 326-330. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165254

Maturana, H. (1997). Emociones y lenguaje en

educación y política [Emotions and language in education and politics]. Dolmen y Granica.

Maureira, F. (2011). Los cuatro componentes de la

relación de pareja [The four

components of the couple relationship].

Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 14(1), 321-332. https://www.iztacala.unam.mx/carreras/psicologia/psiclin/vol14num1/Vol14No1Art18.pdfMcDowell,

T., Knudson‐Martin, C., y Bermudez,

J. (2019). Third‐order

thinking in family therapy: Addressing social justice across family therapy

practice. Family Process, 58(1), 9-22. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12383

Medina, R. (2013). Cultural Sociology

of Divorce. Sage Publications.

Medina, R. (2018). Cambios Modestos, Grandes

Revoluciones. Terapia Familiar Crítica [Modest Changes, Great Revolutions. Critical Family Therapy].

Imagia.

Medina, R. (2022a). La terapia familiar de tercer

orden. Del amor indignado al diálogo solidario. [Third-order family therapy. From indignant love to

solidarity dialogue]. Morata.

Medina, R. (2022b). Introducción a la terapia familiar

de tercer orden: exorcizar a la psicopatología desde la consciencia inter-sistémica. [Introduction to third order family therapy: exorcising psychopathology

from inter-systemic awareness]. Mosaico, 82, 9-30.

Medina, R., Linares, J., Fernández, M., Vargas, E. y

Castro, R. (2018). Nuevo contrato familiar. Fortaleciendo el amor conyugal y la

responsabilidad parental [New family contract. Strengthening marital love and parental responsibility]. Journal of

the Spanish Federation of Family Therapy Associations, 69, 31-51.

Medina, R., Núñez, M., Castro, R. y Vargas, E. (2013).

Pobreza y exclusión social institucionalizada en México: definiciones,

indicadores y dinámica sociológica [Poverty and institutionalized social exclusion

in Mexico: definitions, indicators and sociological dynamics]. In Vargas, E. Agulló, E, Castro, R y Medina, R.

(eds.), Repensando la inclusión social: aportes y estrategias frente a la

exclusión social (pp. 242-268). Eikasia

Ediciones.

Menéndez-Espina, S., Llosa, J. A., Agulló-Tomás, E.,

Rodríguez-Suárez, J., Sáiz-Villar, R., Lasheras-Díez,

H. F., De Witte, H., & Boada-Grau, J. (2020). The influence of gender inequality in the

development of job insecurity: differences between women and men. Frontiers

in Public Health, 8, 526162. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.526162

Minuchin, S. y Nichols, M. (2010). La recuperación de la familia. Relatos de esperanza y renovación [The recovery of the family. Stories of hope and renewal]. Paidós.

Mora, Y., Recalde, D., Montoya, Y., González, M.,

Paternina, D. y Bedolla, L. (2017). Reflexiones sobre la ética del psicológo[Reflections on the ethics of the psychologist]. Poiésis, 33, 59-74. https://doi.org/10.21501/16920945.2496

Núñez, F., Cantó-Milày, N.,

y Seebach, S. (2015). Trust, Lies, and Betrayal. The Role of Trust and Its

Shadows in Couples Relationships. Sociológica,

30(84), 117-142.

Olson, D. H. y Wilson, M. (1982). Family Satisfaction.

In D. H. Olson, H. I. McCubbin, H. Barnes, A. Larsen, M. Muxen y M. Wilson

(eds.). Family inventories: Inventories used in a national survey of

families across the family life cycle (pp. 43-49). University of Minnesota.

Oxford Dictionaries. (2016a). Definition

of admiration in Spanish from the Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved October, 16,

2016 from https://es.oxforddictionaries.com/definicion/admiracion

Oxford Dictionaries. (2016b). Definition

of care in English from the Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved October, 16,

2016 from https://es.oxforddictionaries.com/definicion/cuidar

Pick, S. y Andrade, P. (1988). Desarrollo y validación de la Escala de Satisfacción

Marital [Development and validation

of the Marital Satisfaction Scale]. Psiquiatría,

4(1), 9-20.

Plazaola-Castaño, J., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Montero-Piñar, M. y Grupo de estudio para la violencia de género.

(2008). Apoyo social como factor protector frente a la violencia contra la

mujer en la pareja [Measurement instruments

in family and couples therapy, use of scales]. Gaceta Sanitaria, 22(6), 527-533.

Pozos, J., Rivera, S., Reyes I., y López, M. (2013). Happiness Scale in the Couple: Development

and Validation. Acta de

Investigación Psicológica, 3(3),

1280-1297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2007-4719(13)70967-0

Qian, Y. y Hu, Y. (2021). Couples' changing work patterns in the

United Kingdom and the United States during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Gender,

Work & Organization, 28(S2), 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.

Quees.la. (2013). Significado de querer, concepto y definición - ¿Qué es

querer? [[Meaning of

wanting, concept and definition - What is wanting?] Retrieved October 16, 2016

from http://quees.la/querer/

Reina, J. (2020). El apoyo social en la violencia

de género en relaciones de pareja heterosexual: Caso Bogotá-Colombia

[Social support in gender violence in heterosexual couple relationships: Bogotá-Colombia case] [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Roach, A., Frazier, L. y Bowden, S.

(1981). The marital satisfaction scale: Development of measure for intervention

research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43(3), 537-546.

doi:10.2307/351755

Rodríguez, T. (2019). Imaginarios

amorosos, reglas del sentimiento

y emociones entre jóvenes en Guadalajara [Loving imaginaries, rules of feeling and

emotions among young people in Guadalajara]. Estudios sociológicos, 307(110), 339-367. https://doi.org/10.24201/es.2019v37n110.1683

Rodríguez-Fernández, R. y Ortiz-Aguilar, L. (2018).

Violencia de pareja, apoyo social y conflicto en mujeres mexicanas [Intimate partner violence, social support and conflict in Mexican women]. Trabajo Social Hoy, 83, 7-26. https://doi.org/10.12960/TSH.2018.0001

Rodríguez-Pizarro, A., Rivera-Crespo, J. (2020). Sexual Diversity and Gender Identity:

Between Acceptance and Recognition. Higher Education Institutions. Revista CS, 31, 327-357.

https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i31.3261

Sabbagh, C. y Golden, D. (2021). Justicia distributiva en las relaciones familiares

[Distributive justice in family relations]. Fam. Proc., 60, 1062-1072.

https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12568

Scheinkman, M. (2019) Intimacies: An Integrative

Multicultural Framework for Couple Therapy. Family Process, 58(3),

550-568. doi: 10.1111/famp.12444.

Schreiber, J., Nora, A., Stage, F.,

Barlow, E. y King, J. (2006). Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. The Journal of Educational

Research, 99(6), 323-338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Sluzki, C. (2010). Personal social networks and

health: Conceptual and clinical implications of their reciprocal impact. Family

Systems and Health, 28(1), 1-18 http://doi.org/10.1037/a0019061

Speck, R. & Attneave,

C. L. (1973). Family Networks. Pantheon.