https://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2026.v12.478

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Life satisfaction and

perceived overload as predictors of mental health in caregivers of psychiatric

patients in the Peruvian Andes: A cross-sectional study

Jorge Antonio Calderon Apaza 1, Paul Cristian Alanocca Quispe

1

1 Universidad Peruana Unión, Juliaca, Peru.

* Correspondence: jorge.calderon@upeu.edu.pe

Received: September 03, 2025 | Revised:

December 27, 2025 | Accepted: January 25, 2026 | Published Online: January 26, 2026.

CITE IT AS:

Alanocca Quispe, P., Calderon Apaza, J. (2026). Life

satisfaction and perceived overload as predictors of mental health in

caregivers of psychiatric patients in the Peruvian Andes: A cross-sectional

study. Interacciones,

12, e478. https://doi.org/10.24016/2026.v12.478

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Caregivers of psychiatric patients in the Peruvian Andes face unique

challenges where most people do not receive the necessary health care.

Objective: To analyze the association of life satisfaction and perceived competence

with mental health, determining their incremental explanatory contribution

after controlling for sociodemographic variables and perceived overload.

Method: Cross-sectional study with 102 informal caregivers (85.3% women)

recruited in four Community Mental Health Centers in Puno, Peru. Mental health

(MHI-5), overload (Zarit), life satisfaction (SWLS), and sociodemographic

variables were measured. A hierarchical linear regression analysis with

bootstrapping (5000 samples, BCa) was performed to

handle data non-normality, in addition to non-parametric comparisons

(Kruskal-Wallis).

Results: The final model explained 48.5% of the variance (R² adjusted = .48).

Through bootstrapping, life satisfaction (β =0.41, p <.001) and perceived

competence (β=−0.27, p=.004) showed robust significant associations with mental

health. A displacement effect was observed where overload, significant in the

first model, lost statistical significance (p =.103) upon introducing

psychological resources. Likewise, a low level of instruction (primary and

secondary) remained a significant risk factor compared to higher education.

Conclusion: Self-perception of competence and life satisfaction act as protective

factors that displace the direct impact of perceived overload.

Keywords: Mental health; Life satisfaction; Perceived burden; Caregivers.

INTRODUCTION

Caregivers in Latin America continue to exhibit alarming health

conditions, as they are a valuable yet vulnerable resource (Gaviria et al.,

2023; Montorio et al., 1998). Given that mental health lies in the affective

component of emotions and mood, while the life satisfaction section is a

global, cognitive judgment process in which the individual evaluates the

quality of their existence based on their own criteria and internal standards.

They are forced to reorganize their life and adapt them to the needs of the

dependent, facing a double burden of responsibilities that lead them to assume

new physical, psychological, economic, material, and social demands

(Hernandez-Beltran & Bonilla-Farfan, 2024). Added to this, mental disorders

are found to be the primary disability in the world, as one in eight people

suffers from some mental disorder (World Health Organization [WHO], 2022). Just

in Peru, cases of mental dysfunctions are more than 13 million, with a growing

attention in anxiety (18.81%), depression (13.66%), and Psychological

disorders (14.94%) (Ministry of Health [MINSA], 2025). Moreover, Puno is the

second department in Peru with the most significant care gap, with 89.2% of

people receiving low care, meaning that out of every 10 people, 7 do not

receive the care they require (Defensoría del Pueblo,

2025).

The growth of this problem generates a significant segment of dependent

patients, consequently, the need for more caregivers; however, the majority of

these people lack access to constant and effective care, leading to this labor

being occupied more frequently part by part by family members (Oleas et al.,

2024), who often assume this role without the knowledge or necessary skills,

remaining vulnerable to emotional distress due to drastic changes in their

life, thus affecting their well-being and emotional balance (Peng et al.,

2023). The evidence collected in a Colombian meta-analysis helps us dimension

the problem in similar sociocultural contexts, where 53% of caregivers

experience overload, with 31% at a severe level. Said study profiles the

informal caregiver as a woman (85%) between 18 and 60 years old, who assumes

this responsibility alone (61%), often in conditions of economic vulnerability

(65% in a situation of poverty or extreme poverty) and without access to formal

employment (85%) (Gaviria et al., 2023). In defining the term, informal

caregivers are people who care for someone in their social network, voluntarily

and without direct remuneration (Muñoz et al., 2020; Rogero, 2010). These new

changes and responsibilities are not distributed equitably, thus generating a

primary caregiver, who is the most vulnerable piece of the chain; for this

reason, they are denominated as a silent patient, as they accumulate physical

and psychological ailments, which hide behind the demands of the sick family

member (Tripodoro et al., 2015).

As precedent evidence to this study, the following investigations are

presented as research antecedents. In Asia, the predictability of overload on

the quality of life of 459 caregivers of people with mental illnesses was

investigated, through intermediate variables (anxiety, depression, and

self-esteem), finding a significant relationship of overload to the evaluated

quality of life domains (mental health R² = 0.61, and environment R² = 0.41

social relationships R² = 0.35) demonstrating a high explanatory capacity in

the physical and psychological domains; furthermore, it was identified that

caregivers of schizophrenic patients had a lower quality of life compared to

the rest of disorders (bipolar disorders, severe depression), (Cheng et al.,

2022). Within this line of studies performed, 825 informal caregivers from 6

different countries in Europe were surveyed, the result of the sample of

quality of life related to caregiver health was inversely correlated with

overload with a coefficient (r = -0.180;p< 0.001) evidencing that the

greater the caregiver overload, the lower the quality of life (Valcárcel et

al., 2022). In Valencia, Spain, similar results were found when evaluating 136

primary caregivers; 65.5% of the sample presented elevated levels of overload

affecting mainly psychological health, among the other means evaluated

(physical health, mental health, social relationships, and environment)

(Gallardo et al., 2023). Likewise, within a study in Italy, 91 caregivers of

patients with cognitive disorders and motor disabilities were evaluated, within

this it was found that the most significant predictor among the variables (life

satisfaction, resilience, and depression) of perceived overload was life

satisfaction (β = -0.51, R2 = 0.31) which explained 31% of the variance index

(Fianco et al., 2015). In Germany, 489 informal caregivers were evaluated,

seeking to compare the differences between mental health, quality of life, and

care overload, between genders during the second wave of COVID 19 when caring for

patients ≥60 years; with significant statistical differences in women regarding

men in symptoms: depressive (β = 1.00,p< 0.05), anxious (β = 1.38,p<

0.01), of overload (β = 2.00,p< 0.05) and quality of life (β = −2.16,p<

0.01), finding that women were more prejudiced in their care labor in this

period (Zwar et al., 2023). Thus, a significant correlation is observed between

the patient's degree of dependence and the caregiver's level of overload, as

registered in Cuba, where 68% of caregivers showed being severely overloaded

when caring for totally dependent people (p < 0.05) (Gómez et al., 2024).

This implies that the greater the patient's dependence, the fewer of their

needs the informal caregiver can cover (Duran et al., 2024; Ramos et al.,

2023). On the other hand, Hajek and König (2018) did not find a significant

associative relationship between the start of informal care and the mental

health of caregivers, in their study performed in Germany on 13,300 caregivers;

however, an association was found with their life satisfaction (β = −0.14,p< 0.001).

On the other hand, in Latin America, an investigation was performed in

Nuevo León, Mexico on 210 informal caregivers (family members), significant

negative correlations were found between overload and quality of life (r =

-0.314), physical well-being (r = -0.337), psychological (r = -0.388) and

social (r = -0.287) each element with a significance level (p < 0.001) that

is to say, it presents a moderate and negative relationship between quality of

life and its dimensions (Marroquín et al., 2023). In Nivea, Colombia, 68

caregivers participated in a study that found a low, statistically significant

relationship between overload and well-being: physical (r = 0.333),

psychological (r = -0.122), and social (r = 0.541) (Cantillo et al., 2022).

Also in Buenos Aires, Argentina, a study was performed in which overload was

evaluated in 64 primary caregivers, the quality of life and their coping

strategies, in which a significant negative correlation was evidenced between

overload and the dimension of psychological health (r = -.38; p = 0.002) (Hauché et al., 2025).

For this study purpose, a psychiatric patient is someone with a

diagnosed mental disorder whose severity, persistence, and functional impact

place them in a severe or grave category (Pina et al., 2024). This excludes

personality disorders (except schizotypal), substance abuse, disorders without

psychotic symptoms, eating disorders, and recurrent depression (UK National

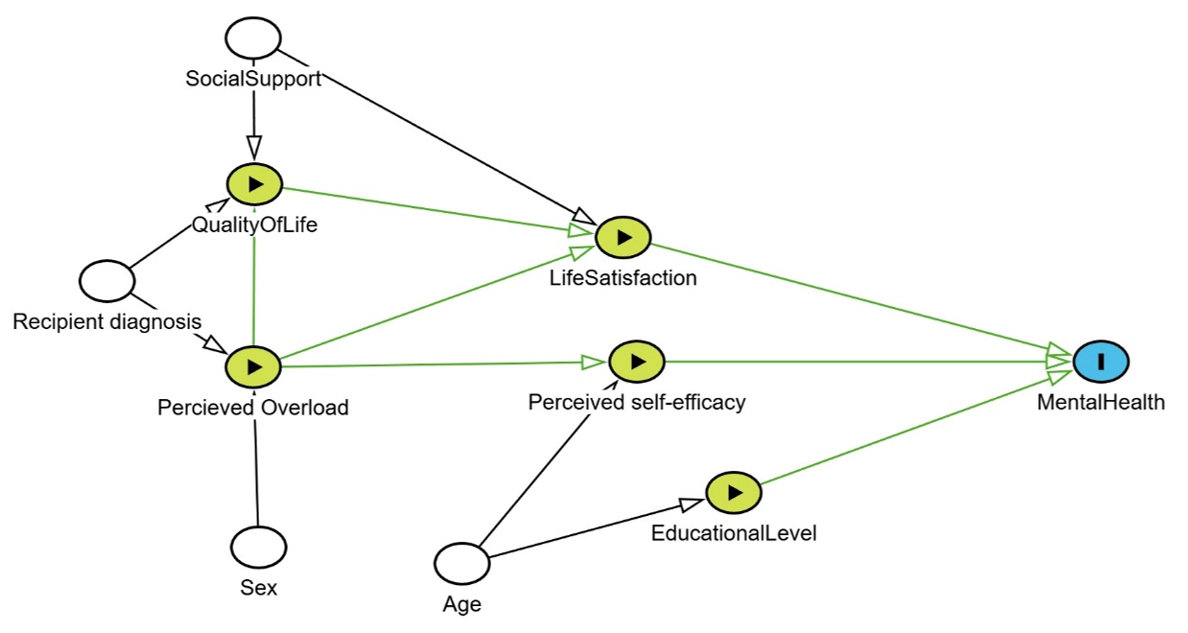

Health Service [NHS], 2024). To furthermore clarify the conceptual mechanisms

and justify the selection of variables, a theoretical Directed Acyclic Graph

(DAG) is presented (Figure 1). Where the variables influential to Mental health

are hypothesized. In response to the need for parsimony, Life Satisfaction was

prioritized over broader constructs like 'Quality of Life'; as it is a global

construct that houses different thematic fields (Ramirez et al., 2019); while

Life Satisfaction represents the specific cognitive judgment (Baghino & Cortelletti, 2021);

which directly mediates the impact of external circumstances (Overload) on

Mental Health. Likewise, other factors like self-esteem and being dependent on

external feedback are exposed to short-term fluctuations (Hank & Baltes,

2019), making their evaluation in relation to mental health difficult.

Sociodemographic variables that did not show direct theoretical relevance in

the context of the clinical sample studied were omitted.

Figure 1. Directed

acyclic graph.

Note: The nodes represent the variables observed in the

study. The green arrows indicate the direct causal trajectories estimated in

the regression model.

Despite the growing importance of mental health, previous evidence, both

national and international, on the subject has not addressed the joint

interaction of our variables as factors associated with the psychological

well-being of caregivers. Added to that, most of these investigations focus on

caregivers of people dependent due to physical disabilities, where overload is

addressed as a purely global construct. In this way, research on caregivers of

people with severe mental disorders is limited, especially in Perú, where

current articles on the subject are scarce. This research contributes a new

perspective by analyzing caregivers of psychiatric patients in the Andean

context of low resources, demonstrating through a hierarchical analysis that

the self-perception of competence possesses a displacement effect on overload,

which will allow a deeper and more updated understanding of the dynamics of

life satisfaction, perceived overload, and mental health in caregivers. This

reorients clinical intervention priorities in the region: programs should not

focus solely on care overload, but predominantly on skills training and

cognitive reinforcement of life satisfaction to shield the caregiver's mental

health.

In this way, the research had as a general objective, to analyze the

association of Life Satisfaction and Perceived Competence with Mental Health,

determining their incremental explanatory contribution when controlling for the

effect of the Degree of Instruction, the Patient's Diagnosis, and Perceived

Overload; and as specific objectives: To evaluate the initial association of

sociodemographic variables (degree of instruction and patient's diagnosis) and

perceived overload with the caregiver's mental health; To determine the

incremental explanatory contribution of psychological resources (life

satisfaction, competence, and interpersonal relationships) in the variance of

mental health, and To compare the levels of mental health, overload, and

psychological resources according to the diagnosis of the care receiver

(Schizophrenia, ASD, and others) to identify significant differences between

groups.

METHODS

Design

The study is developed using a quantitative approach, with a

non-experimental, cross-sectional design. It is framed within an

associative-predictive strategy, as defined by Ato et al. (2013), since it

seeks to estimate the degree of association between a criterion variable and

multiple independent variables.

Participants

The population consists of 102 caregivers of users with open or current

medical records at the 4 community mental health centers operating in Juliaca in 2025. Data was collected between May and July,

with authorization from the network coordination and the heads of each center.

Inclusion criteria used were (full-time or part-time caregivers of dependent

people due to a diagnosed psychiatric disorder, of both sexes; caregivers who

have reached the age of majority, 18 years; having provided care to the user for

at least 3 months; and having informed consent); as exclusion criteria, it was

established: (That the caregiver has some permanent or temporary disability

that prevents answering the tests' questions coherently, having cared for the

user for less than 3 months; patient receives less than 2 psychotherapeutic

sessions per month; patient does not have a psychiatric diagnosis).

To calculate the minimum sample size necessary for the theoretical

model, the software G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2009) was used with the

following parameters (f²) = 0.35, (α) = 0.05, (1- β) = 0.95, N° predictors 10,

obtaining a minimum required participants of 77; which allows performing the

study with sufficient statistical significance (Cohen, 1992). Thus, the sample

was estimated by a non-probabilistic convenience sampling, based on the

researchers' selection criteria and resources (Otzen & Manterola, 2017).

Variables

The consequences of living with a person affected by some severe

illnesses are known as "care overload" or "family burden",

which encompasses the subjective and objective conditions the caregiver goes

through (Gulayín, 2022). Perceived overload is a

state of feeling sad, stressed, and constantly frustrated experienced by a

caregiver of someone dependent, as this definition encompasses not only the

clinical field but also the social and economic spheres (Márquez et al., 2025).

In the same way, burden refers to emotional and physical health alterations

that occur when demands exceed available resources (Sánchez et al., 2016).

On the other hand, the Pan American Health Organization (2023) states

that mental health is a state of emotional well-being that enables people to

face difficult moments in life through the development of skills, which are a

fundamental mechanism for adequate coexistence in a community. Being that

well-being and health are individual capacities. Furthermore, satisfaction is

defined as a mental state, a positive valuation of something. The term

encompasses both this context and that of "enjoyment", integrating

both cognitive and emotional appreciations (Veenhoven,

1994). Under that proposal, life satisfaction is understood as a judgment that

endures in a time-dependent context, in which the person values their

well-being by comparing their standards of living with their current situation

(Calderón et al., 2018). Therefore, satisfaction is important because it

reflects the cognitive equilibrium between adequate achievement and personal

expectations (Mikulic et al., 2019).

Instruments

To evaluate life satisfaction, the questionnaire (SWLS) Satisfaction

With Life Scale was used, created by Diener et al. (1985); due to the need to

measure how satisfied the population is with their life coming to possess

multiple items, this was designed to evaluate the general opinion of life is an

individual to evaluate individual satisfaction; it was based on the concept of

life satisfaction by Shin and Johnson (1978) who define it as: "A global

assessment of a person's quality of life according to their chosen

criteria." Previously validated in various Peruvian studies, including

that of Calderón et al. (2018), which presented adequate goodness-of-fit

indices (GFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.073, SRMR = 0.067). Likewise, it has reported

optimal reliability (ω = 0.90) in a population aged 19 to 64 years. Finally, it

indicates that the instrument evaluates in one dimension the satisfaction with

life with a multiple response scale as an ordinal measure of five response

options under the Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = slightly disagree, 3

= neither agree nor disagree, 4 = slightly agree, 5 = strongly agree. In the

present research, internal consistency indices of Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.731)

and McDonald’s omega (ω = 0.740) were obtained.

On the other hand, to evaluate the perceived overload variable, the

Zarit Burden Interview was used, which was originally developed by Zarit et al.

(1980). This has the purpose of explaining how mental, physical health, and

labor and economic aspects are compromised when caring for a sick person with

dementia. In the Peruvian context, it was validated previously in a population

of caregivers with intellectual disability of 398 informal caregivers between

24 and 65 years old. The instrument consists of 15 items across 4 dimensions:

overload, competence, social relationships, and interpersonal relationships.

These items have Likert response options: (0 = Never, 1 = Rarely, 2 =

Sometimes, 3 = Often, 4 = Almost always). Regarding the validity evidence,

goodness-of-fit indices were found (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.055, TLI = 0.94),

with optimal reliability evidence (ω = 0.740) (Domínguez et al., 2023). For the

current population, internal consistency indices of Cronbach's alpha (α) =

0.863 and McDonald's omega (ω) = 0.866 were obtained.

Finally, to evaluate mental health, the Mental Health scale MHI-5 was

used, the original version created by Berwick et al. (1991), validated in the

Peruvian context in the adult population, between the ages of 17 and 45 years

by Vilca et al. (2022). It is a brief measure composed of five items, with a

Likert-type response format and four options (never, sometimes, often, and

always), where never is worth 0 and always is worth 3. In the adaptation study,

the scale evidenced adequate psychometric properties. In relation to construct

validity, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed, yielding adequate fit

for the proposed unidimensional model (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, and RMSEA =

0.07). For the present research, internal consistency indices of Cronbach's alpha

(α = 0.773) and McDonald's omega (ω = 0.790) were obtained.

Data analysis

After collecting the data through surveys and individual interviews, the

data were transcribed manually into Microsoft Excel, ensuring that each item

column was correctly coded to the pertinent scales. For data analysis, Jamovi 2.3.28.0 software and JASP 0.95 were used. The

grouped discrete variables were analyzed using measures of central tendency,

dispersion, and distribution (skewness, kurtosis, quartiles, mean, median, and standard deviation). Furthermore, the univariate

normality of the variables was checked under the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

(Hernández et al., 2014). This suggests a non-normal distribution, as the

significance levels exceed the 0.05 threshold. Given the non-normality in two

variables, Spearman's Rho correlation coefficients were used.

After that, a Hierarchical Linear Regression with Bootstrapping (5000

resamples) of the BCa type was performed to account

for the nonparametric nature of the data. Variables were introduced in two

functional blocks. In Block 1, control variables (Degree of instruction, Care

hours, Patient disorder) and overload were included. In Block 2, psychological

resources (Competence, Life satisfaction, Social and interpersonal

relationships) were added. The categorical variables (Degree of instruction and

Patient diagnosis) were transformed into dummy variables for the regression

analysis, using 'Higher Education' and 'Schizophrenia' as reference categories,

respectively. After that, the change in R2 (ΔR2) were analyzed, additionally,

the assumptions of multiple linear regression were verified as pointed out by

Vila-Baños et al., (2019), including linearity, normality of residuals,

homoscedasticity, independence of errors and absence of multicollinearity of

independent variables; finally, the analysis of unstandardized coefficients was

performed to quantify the predictability between the variables.

Ethical considerations

The present research was submitted to the Ethics Committee of the

Faculty of Health Sciences of the Universidad Peruana Unión for subsequent

approval under resolution N°2025-CEB-FCS – UPeU-075. Furthermore, the

parameters of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association

(WMA, 2024) are followed, where human rights in research are held as priority,

safeguarding integrity, health, dignity, privacy, as well as confidentiality of

all participants, reaching a great responsibility as researchers protecting the

obtained information. Only coming to use it for research purposes, this with

the backing of the College of Psychologists of Peru, which according to chapter

10 of the code of ethics and psychological deontology, confidentiality is a

crucial point not to identify the participants, ethnic group or institution,

respecting the autonomy of the respondents and participants through obtaining

informed consent prior to their participation, guaranteeing their understanding

of the study objectives, and their right to refuse or withdraw at any moment

(Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú, 2017).

RESULTS

102 informal caregivers of users of community mental health centers were

surveyed; based on the results, a data matrix inspection was performed prior to

the inferential analysis. No missing values were detected (0% of missing data)

in the study variables, which is attributed to the face-to-face data collection

strategy performed by trained personnel, who verified the completeness of the

questionnaires in situ. The surveyed caregivers had an average age of 39.8 (SD

= 9.79) years, of whom 85.3% are of the female gender, which is equivalent to

(87 caregivers), while 14.7% represent the male gender with (15 caregivers);

the most common patient-caregiver relationship found was that of parents with

78.4% (n=80), followed by siblings 9.8% (n=10), with 11.8% (n=12) being

children, partners, and other immediate family members; on the other hand, the

time of care most found was between 4 to 10 years with 50% (51) followed by 1

to 3 years with 41.2% (n=42), more than 10 years are 3.9% (4). In the degree of

instruction, it was found that 47.1% (n=48) have complete secondary studies,

33.3% (n=40) pursued higher studies, 12.7% (n=13) have complete primary

studies, 1% (n=1) have incomplete primary studies; in the religion section,

86.3% (88) claim to be Catholic, 3.9% (n=4) are Christian, and 2.9% (n=3) are

Adventist. The caregiver's place of residence is 91.2% (n=93) in Juliaca, 8.8.% (n=9) live in other provinces (Moquegua,

Tacna, Arequipa, Moho), finally in the section of dependent's disorders, 38.2%

(n=39) present schizophrenia, 37.3% (n=38) suffer from ASD, 10.8% (n=11) belong

to ADHD, 13.7% (n=14) present other psychiatric disorders.

When distributing the scores of overloads, life satisfaction,

competence, social and interpersonal relationships, according to the care

receiver's diagnosis in three groups: schizophrenia (n = 39), autism spectrum

disorder (ASD, n = 38), and other diagnoses (n = 25), the descriptive analysis

of the variables showed similar average scores. The non-parametric Kruskal

Wallis statistical analysis confirmed that these differences were not

significant regarding the dimensions of: Overload (X² =0.87,p =

.647); life satisfaction (SWLS) (X² = 2.70,p = .259); competence

(X² = 2.11,p = .348) nor social relationships (X² = 3.51,p

= .173); but there were significant variations regarding the interpersonal

relationship with the care receiver (X² = 6.68,p = .035), where

caregivers of people with schizophrenia present the highest average (M = 5.90,

Me = 7), while Other diagnoses presented the lowest levels, being in turn the

most heterogeneous group (M = 3.92, ME = 3, SD = 3.17).

In Table 1, the assumption of normality was calculated through the Z

statistic, obtained by dividing the skewness and kurtosis values by their

respective standard errors. Considering a significant and non-normal deviation

if the value exceeds ±2 (George & Mallery, 2003). Under said criteria, the

variables of mental health, life satisfaction, overload, and social

relationships found normal values in both skewness and kurtosis; however,

deviations from normality were observed in the competence variable, with a

significant negative skewness (Z = -2.27) with a tendency towards high scores;

as well as in the variable of interpersonal relationships, where a significant

negative kurtosis was found (Z = -2.01), suggesting a platykurtic distribution.

Table 1. Table of normality

of variables.

|

|

Skewness |

kurtosis |

||||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Value |

SE |

Value |

SE |

|

Mental

health |

6.48 |

3.22 |

0.36 |

0.24 |

-0.57 |

0.47 |

|

Life

satisfaction |

13.08 |

3.78 |

0.39 |

0.24 |

0.01 |

0.47 |

|

Overload |

8.45 |

3.40 |

-0.15 |

0.24 |

-0.55 |

0.47 |

|

Competence |

12.32 |

3.97 |

-0.54 |

0.24 |

-0.35 |

0.47 |

|

Social

relationship |

6.03 |

2.88 |

-0.13 |

0.24 |

-0.85 |

0.47 |

|

Interpersonal

relationship |

5.19 |

3.02 |

-0.17 |

0.24 |

-0.95 |

0.47 |

Table 2 shows the correlations among the three variables and dimensions

(overload, competence, social relationships, and interpersonal relationships).

Life satisfaction and mental health show a moderate positive correlation.

Likewise, life satisfaction and mental health correlate inversely with

perceived caregiver overload and its dimensions, indicating that, at higher

levels of life satisfaction and mental health, they are associated with lower

perceptions of caregiver overload, and vice versa.

Table 2. Table of

correlations.

|

|

SWLS |

CI 95% |

Mental

Health |

CI 95% |

|

Mental

health |

0.535 (<

.001) |

0.371 to

0.655 |

– |

– |

|

Overload |

-0.328

(< .001) |

-0.202 to

-0.536 |

-0.265

(< .007) |

-0.122 to

-0.475 |

|

Competence |

-0.345

(< .001) |

-0.175 to

-0.516 |

-0.468

(< .001) |

-0.356 to

-0.645 |

|

Social

relationships |

-0.383

(< .001) |

-0.217 to

-0.547 |

-0.290

(< .003) |

-0.164 to

-0.508 |

|

Interpersonal

relationships |

-0.182

(< .067) |

0.008 to

-0.368 |

-0.395

(< .001) |

-0.225 to

-0.553 |

The five assumptions of regression were considered: linearity,

independence of errors, homoscedasticity, normality, and non-multicollinearity,

all of which were met (Vila et al., 2019).

In Table 3, the first block explained 20.9% of the variance. The

inclusion of the psychological variables in the second block significantly

increased the model's explanatory capacity by an additional 32.5%. The change

in R² (ΔR² = .325, p < .001) was significant, indicating that

the psychological variables contribute an additional 32.5% of unique

explanation to the model.

Table 3. Model

summary.

|

Model |

R |

R square |

R square

adjusted |

RMSE |

|

M1 |

0.455 |

0.207 |

0.166 |

2.939 |

|

M2 |

0.729 |

0.531 |

0.485 |

2.308 |

As observed in Table 4, after applying bootstrapping, in Model 1,

overload was a significant negative predictor (β = -.265; 95% CI BCa [-.446, -.058]; p = .011), indicating that, when

considering only basic variables, greater overload is associated with lower

mental health. Likewise, the degree of instruction showed a considerable

association, with having only completed primary education versus complete higher

education associated with lower mental health (β = -3.251; 95% CI BCa [-5.203, -1.373]; p = .002). In the same way,

having a complete secondary education as the highest educational level

obtained, versus having complete higher education, predicted lower mental

health (β = -1.98; 95% CI BCa [-3.39, -.49]; p =

.001). Upon introducing the psychological resources in Model 2, the caregiver's

degree of instruction emerged as the most robust associated factor, where

caregivers with complete primary education versus those with completed higher

education, presented lower indices of mental health (β = -2.19; 95% CI BCa [-3.75, -.7];p= .004), similar results were

observed when comparing complete secondary education versus complete higher

education (β = -2.09; 95% CI BCa [-3.264, -.99];p<

.001), followed by competence (β = -.27; 95% CI BCa

[-.43, -.08];p= .003) and life satisfaction (β = .41; 95% CI BCa [.26, .55];p< .001). After the inclusion of

these psychological resources, the overload dimension ceased to be

statistically significant (β = -.17; 95% CI BCa

[-.04, .37]; p = .112). The dimensions of Social and Interpersonal

Relationships did not result in significant differences.

Table 4. Hierarchical

Multiple Regression

|

Model |

|

β (CI 95%) |

Bias |

SE |

p |

|

M1 |

(Intercept) |

10.689

(8.298 to 12.572) |

-0.01 |

1089.00 |

< .001 |

|

Overload |

-0.265

(-0.446 to -0.058) |

0.00 |

0.10 |

0.011 |

|

|

Others -

schizophrenia |

-0.507

(-2.093 to 1.043) |

-0.02 |

0.80 |

0.526 |

|

|

ASD -

schizophrenia |

-0.907

(-2.506 to 0.647) |

-71.21 |

0.80 |

0.226 |

|

|

Primary

education - higher education |

-3.251

(-5.203 to -1.373) |

-0.01 |

0.97 |

0.002 |

|

|

High school

- higher education |

-1.983

(-3.389 to -0.487) |

-0.01 |

0.74 |

0.010 |

|

|

M2 |

(Intercept) |

5.959

(2.694 to 9.304) |

0.01 |

1692.00 |

< .001 |

|

Overload |

0.169

(-0.043 to 0.374) |

-0.01 |

0.11 |

0.112 |

|

|

Others -

schizophrenia |

-1.212

(-2.532 to 0.125) |

-0.01 |

0.68 |

0.075 |

|

|

ASD -

schizophrenia |

-1.166

(-2.424 to 0.016) |

-0.01 |

0.62 |

0.053 |

|

|

Primary

education - higher education |

-2.193

(-3.745 to -0.700) |

-0.04 |

0.78 |

0.004 |

|

|

High school

- higher education |

-2.092

(-3.264 to -0.999) |

0.00 |

0.57 |

< .001 |

|

|

SWLS |

0.409

(0.265 to 0.553) |

0.00 |

0.07 |

< .001 |

|

|

Self competence |

-0.274

(-0.432 to -0.083) |

0.00 |

0.09 |

0.003 |

|

|

Social

relationships |

-0.001

(-0.234 to 0.217) |

0.00 |

0.11 |

0.999 |

|

|

Interpersonal

relationship |

-0.153

(-0.369 to 0.093) |

0.01 |

0.12 |

0.192 |

Note:

Bootstrapping based on 5000 samples. Schizophrenia and completed higher

education were used as reference variables.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the degree of association of

life satisfaction and perceived overload on mental health. For this, a multiple

linear regression model was estimated which explained 48.5% of the variance,

where it was observed that life satisfaction (β = .41; 95% CI BCa [.26, .55];p< .001), the caregiver's self-perception

of competence (β = -.27; 95% CI BCa [-.43, -.08];p=

.003) and the level of instruction, compared between primary education to

completed higher education (β = -2.19; 95% CI BCa

[-3.75, -.7];p= .004) and secondary education to completed higher education (β

= -2.09; 95% CI BCa [-3.264, -.99];p< .001) were

significantly associated with mental health.

Competence showed a negative association regarding mental health (β =

-.27; 95% CI BCa [-.43, -.08]; p= .003). In line with

previous investigations, it was identified that self-efficacy was significantly

related to the mental health of caregivers, β = .10 (p = .001) (Clarke et al.,

2021), as well as negatively to depressive symptoms (β = -1.647; p< .001)

(Tang et al., 2015). Suggesting that, the negative perception a person has

about their capacity to provide care (Albarracín et al., 2016), or the

"competence" factor, is directly associated with their mental health.

Determining their level of motivation and confidence, thus beliefs in personal

capacities can transform apparently threatening situations into manageable

situations, preventing risky behaviors and promoting adaptive behaviors

(Zenteno et al., 2017). On the other hand, under Ellis's parameters, this lack

of confidence in one's own skills would be in irrational beliefs such as

perfectionist expectations (Ellis & Grieger, 1981). These results position

the caregiver's perception of their own capacities as a mechanism strongly

associated with their mental health.

Subsequently, life satisfaction was the second most robust positive

relationship (β = .41; 95% CI BCa [.26, .55];p< .001), which is in line with other studies in

informal caregivers in the Netherlands, where life satisfaction was

significantly associated with psychological well-being (β = .155, p= .016) (Bremmers et al., 2024). That suggests that life

satisfaction, which is the comparison between the individual's subjective

standard and their personal circumstances (Diener et al., 1985), acts as a

positive psychological resource for the caregiver; in other words, maintaining

standards close to their current life condition (Calderón et al., 2018). It

acts as a resilience-promoting factor (WHO, 2022), making life satisfaction a

significant and protective factor for the mental health of caregivers.

The caregiver's level of instruction was negatively and significantly

associated with mental health when comparing completed higher education

(reference group) against completed primary education (β = -2.19; 95% CI BCa [-3.75, -.7];p= .004) and against completed secondary

education (β = -2.09; 95% CI BCa [-3.264, -.99];p<

.001), evidencing that caregivers with a lower educational level are associated

with worse mental health. In the same line of research, there are precedents

that the highest educational level obtained acts as a protective factor against

various disorders, such as major depression, alcohol dependence, generalized

anxiety, ADHD, and PTSD (Demange et al., 2024), for it is associated with

better cognitive skills, emotional regulation and cooperation which is linked

to better mental health (Jareebi et al., 2024). This

phenomenon is especially seen in women of primary or lower educational levels

since they are 86% more prone to suffering anxious or depressive disorders (Bacigalupe et al., 2020).

Finally, the non-significance of the overload score in our final model

is of particular interest (β = -.17; 95% CI BCa

[-.04, .37]; p= .112), for it disagrees with similar studies, where the

overload coefficient on mental health or psychological well-being was: β =

-.40, p< .001 (Nah et al., 2022). β = -.294, p< .001 (Bremmers

et al., 2024) β = -.262; p= .001 (Agyemang et al., 2024). Furthermore,

literature on caregiver well-being has consistently established overload as a

variable related to negative results in mental health or psychological

well-being, as it is associated with symptoms of sadness, feelings of burden,

and stress (Marquéz, 2025). In our results, a

displacement effect is observed due to the statistical control of variables

(Becker, 2005). While in the first model a significant negative association was

observed between overload and mental health (β = -.264; 95% CI BCa [-.45, -.06]; p = .017), the effect disappeared upon

introducing the other psychological resource variables (p = .112). Especially

the "competence" variable, which, due to its specificity, seems to

capture the variance associated with mental health that, otherwise, would be

attributed to overload. This relationship is not commonly explored due to

methodological limitations rooted in the original Zarit test's global overload

score (Zarit et al., 1980), and it does not imply that care overload is

irrelevant; instead, it suggests that the caregiver's perception of competence

is a more robust protective factor. This theoretical model would explain why a

direct relationship between providing informal care and the caregiver's mental

health is not always found (Hajek and König, 2018).

Limitations

and strengths

The present study must be interpreted considering the methodological

limitations presented. The cross-sectional design prevents the observation of

variables over time; furthermore, an influence of third variables, mediating

variables, or reverse directionality not measured cannot be ruled out;

furthermore, the selection of the sample being non-probabilistic by convenience

limits generalizing findings to the general population of caregivers of the

region (Etikan et al., 2016). At the same time, the

selection bias inherent to intrahospital recruitment is recognized, considering

a regional mental health care gap of 89.2% (Defensoría

del Pueblo, 2025), which excludes caregivers without access to the formal

system. Likewise, the instruments (SWLS, Zarit, and MHI-5) have national

validation; the lack of specific adaptation to the Andean context could

introduce cultural or linguistic biases in the local population's

interpretation of the items.

Just as the mentioned limitations, the study also possesses several

notable strengths; the main one is the analytical approach that allows the

deconstruction of the concept of overload, since the version of the Zarit

instrument by Albarracín et al. (2016) does not measure overload as a global

construct. However, as a further dimension, by isolating its components, we

managed to discern which exerts the greater effect within the proposed model,

offering a view of the specific psychological mechanism of association, moving

away from the traditional approach predominant in the literature. On the other

hand, data collection was conducted by trained personnel in a face-to-face and

individual manner, ensuring the quality of the collected information.

Recommendations

Based on the results, it is recommended that interventions for

caregivers of psychiatric patients focus on strengthening perceptions of

competence, increasing life satisfaction, and facilitating access to

educational opportunities. At an individual level, caregivers must receive

practical, continuous training that helps them feel secure in their role, as

well as psychological support and self-care spaces that enhance their overall

well-being. For researchers, beyond the direct relationships between competence

and mental health and between life satisfaction and mental health, it would be

helpful to investigate variables that mediate or moderate those relationships.

On the other hand, public entities should implement accessible training

programs, create emotional support networks, and offer services that foster a

balance between personal life and care. Finally, at the level of public

policies, it is proposed to formally recognize the caregiver's role, develop

interventions centered on the improvement of perceived competence and life

satisfaction, and include indicators like life satisfaction and perception of

competence in institutional evaluations, to ensure integral and sustainable

accompaniment of those who fulfill this essential labor in the mental health system.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the mental health of caregivers

in the sample studied is strongly associated with their level of instruction,

life satisfaction, and self-perception of competence, and the final model

presented explained 48.5% of the variance.

ORCID

Jorge Antonio Calderon Apaza: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-9615-004x

Paul Cristian Alanocca Quispe: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0881-4610

AUTHORS’

CONTRIBUTION

Jorge Antonio Calderon Apaza: Manuscript

conception; Data collection; Data analysis and interpretation; Manuscript

writing.

Paul Cristian Alanocca

Quispe: Manuscript conception; Data collection; Data analysis and

interpretation; Manuscript writing.

FUNDING SOURCE

This paper was self funded and supported by “Universidad Peruana Unión” in

collaboration with “Red de salud San Roman”.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there were no conflicts of

interest in the collection of data, analysis of information, or writing of the

manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by two external reviewers in double-blind

mode. The editor in charge was David Villarreal-Zegarra. The review process is included

as supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors attach the

database as supplementary material 2.

DECLARATION OF THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

We used DeepL to translate specific sections of the manuscript and

Grammarly to improve the wording of certain sections. The final version of the

manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Albarracín Rodríguez, Á., Cerquera Córdoba, A., & Pabón

Poches, D. (2016). Escala de sobrecarga del cuidador Zarit: Estructura

factorial en cuidadores informales de Bucaramanga. Revista de Psicología

Universidad de Antioquia, 8(2), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rpsua.v8n2a06

Agyemang-Duah, W., Oduro, M. S., Peprah,

P., Adei, D., & Nkansah, J. O. (2024). The role of gender in health

insurance enrollment among geriatric caregivers: results from the 2022 informal

caregiving, health, and healthcare survey in Ghana. BMC Public Health, 24(1),

1566. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18930-y

Asociación Médica Mundial. (2024). Declaración de Helsinki. http://www.wma.net/s/ethicsunit/helsinki.htm

Ato, M., López, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de

clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de

Psicología, 29(3), 1038-1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Bacigalupe,

A., Cabezas, A., Bueno, M. B., & Martín, U. (2020). El género como

determinante de la salud mental y su medicalización. Informe SESPAS 2020.

Gaceta sanitaria, 34, 61-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2020.06.013

Baghino,

D., & Cortelletti, L. (2021). Satisfacción vital

y felicidad en primera y seguna ola de la pandemia

por COVID-19. Anuario de Investigaciones, 28(1), 339–346.

Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the

statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative

analysis with recommendations. Organizational research methods, 8(3),

274-289.

Berwick, M., Murphy, M., Goldman, A., Ware, E.,

Barsky, J., & Weinstein, C. (1991). Performance of a Five-Item Mental

Health Screening Test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008

Bremmers, L. M., Fabbricotti, I. N., & Hakkaart,

L. (2024). The impact of informal care provision on the quality of life of

adults caring for persons with mental health problems:

A cross-sectional assessment of caregiver quality of life. SAGE Open Nursing, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20551029241262883

Calderón-De la Cruz, G., Lozano Chávez, F., Cantuarias Carthy, A.,

& Ibarra Carlos, L. (2018). Validación de la Escala de Satisfacción con la

Vida en trabajadores peruanos. Liberabit,

24(2), 249-264. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2018.v24n2.06

Cantillo-Medina, P., Perdomo-Romero, Y., & Ramírez-Perdomo, A.

(2022). Características y experiencias de los cuidadores familiares en el

contexto de la salud mental. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y

Salud Pública, 39(2), 185-192. http://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2022.392.11111

Cheng, C., Chang, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Yen, C. F.,

Liu, H. C., Su, J. A., Lin, C. Y., & Pakpour, A.

H. (2022). Quality of life and care burden among family caregivers of people

with severe mental illness: Mediating effects of self-esteem and psychological

distress. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 672. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04289-0

Clarke, R., Farina, N., Chen, L., Rusted, M., &

IDEAL program team. (2021). Quality of life and well-being of carers of people

with dementia: are there differences between working and nonworking carers?

Results from the IDEAL program. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(7),

752-762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820917861

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological

Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú. (2017). Código de Ética y Deontología Profesional. Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú.

Defensoría del Pueblo. (2025, 10 de octubre). Defensoría del

Pueblo reitera necesidad de fortalecer la Dirección de Salud Mental para

superar las brechas en materia de atención a pacientes. https://www.defensoria.gob.pe/defensoria-del-pueblo-reitera-necesidad-de-fortalecer-la-direccion-de-salud-mental-para-superar-las-brechas-en-materia-de-atencion-a-pacientes/

Demange, P. A., Boomsma, D. I., van Bergen, E., &

Nivard, M. G. (2024). Evaluating the causal relationship between educational

attainment and mental health. medRxiv, 2023-01. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.26.23285029

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S.

(1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment,

49(1), 71-75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Domínguez, J., Santa-Cruz, H., & Chávez, V.

(2023). Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview: Psychometric Properties in Family

Caregivers of People with Intellectual Disabilities. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ., 13(2), 391-402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13020029

Duran, T., Llorente, Y., & Romero, I. (2024). Dependencia funcional del receptor del cuidado, sobrecarga y

calidad de vida del cuidador de personas con tratamiento sustitutivo renal. Revista

Salud Uninorte, 40(2), 416-430. https://doi.org/10.14482/sun.40.02.357.753

Ellis, A., & Grieger, R. M. (Eds.).

(1981). Manual de terapia racional-emotiva (Vol. 1). Desclée De Brouwer.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience

sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied

Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang,

A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for

correlation and regression analyses. Behavior research methods 41(4),

1149-1160 https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Fianco, A., Sartori, D., Negri, L., Lorini, S., Valle,

G., & Delle Fave, A. (2015). The relationship

between burden and well-being among caregivers of Italian people diagnosed with

severe neuromotor and cognitive disorders. Research in developmental

disabilities, 39, 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.01.006.

Gallardo J., Bravo , J., Gallego, J., & Guitiérrez, J.

(2023). Calidad de vida y sobrecarga en el

cuidador principales. Journal Nursing, 2952-3192.

Gaviria, D., Moreno, S., & Díaz, L. (2023). Sobrecarga del

cuidador familiar en Colombia: revisión sistemática exploratoria. Revista

colombiana de enfermería, 22(1), 17-31. https://doi.org/10.18270/rce.v22i1.3754

Gómez-Soler, U., Hierrezuelo-Rojas, N.,

Hernández-Magdariaga, A., Acosta-Montero, D., Ramos-Isacc, Y., &

Trujillo-Moreno, Y. (2024). Sobrecarga en cuidadores primarios de adultos

mayores dependientes. Archivo Médico Camagüey, 28, e10021.

Gulayín,

M. (2022). Carga en cuidadores familiares de personas con esquizofrenia: una

revisión bibliográfica. Vertex Revista Argentina de

Psiquiatría, 33(155), 50-65. https://doi.org/10.53680/vertex.v33i155.135.

Hank, P., &

Baltes-Götz, B. (2019). The stability of self-esteem variability: A

real-time assessment. Journal of Research in Personality, 79, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.03.004

Hajek, A., & König, H. (2018). The relation

between personality, informal caregiving, life satisfaction and health-related

quality of life: evidence of a longitudinal study. Quality

of Life Research, 27, 1249-1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1787-6.

Hauché, A., Chiaramonte, A., Galvagno,

G., & Isabel, G. (2025). Sobrecarga,

calidad de vida y estrategias de afrontamiento en cuidadores primarios de

pacientes crónicos. Revista Iberoamericana ConCiencia,

10(1), 42-60. https://doi.org/10.70298/ConCiencia.10-1.5.

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista

Lucio, P. (2014). Definiciones de los enfoques cuantitativo y cualitativo, sus

similitudes y diferencias. En Metodología de la investigación (6.ª ed., pp.

2-21). McGraw-Hill.

Hernandez-Beltran, K., & Bonilla-Farfan, D. (2024). Percepción

de la carga del cuidador familiar de personas con alteraciones en la salud

mental. Boletín Semillero de Investigación en Familia, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.22579/27448592.1137.

Jareebi, M. A., & Alqassim, A.

(2024). The impact of

educational attainment on mental health: A causal assessment from the UKB and FinnGen cohorts. Medicine, 103(26), e38602. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000038602

Márquez, A. (2025). Revisión de la evidencia empírica relacionada

con el síndrome de sobrecarga del cuidador publicada en los últimos diez años. Trabajo

Social Hoy, 103(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.12960/TSH.2025.0001

Márquez, V., Calderon, C., & Agustin, E. (2025). Círculo

vicioso de la enfermedad. El nivel de sobrecarga del cuidador primario del

paciente oncológico pediátrico. Salud Publica y enfermedades, 116 - 152.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12866/3973

Marroquín-Escamilla, R., Santos-Flores, M., Montes de Oca Luna,

R., Santos-Flores, I., Obregón Sánchez, N. H., & Trujillo-Hernández, P. E.

(2023). Calidad de vida y sobrecarga de cuidadores familiares en primer nivel

de atención. Revista Salud Uninorte, 40(2), 416-430. https://doi.org/10.14482/sun.40.02.357.753

Mikulic, M., Crespi, M., & Caballero, Y. (2019). Escala de

satisfacción con la vida (SWLS): Estudio de las propiedades psicométricas en

adultos de Buenos Aires. Anuario de investigaciones, 26, 395-402.

Ministerio de Salud. (2025, 10 de

enero). Establecimientos del Minsa atendieron más de 250 000 casos de

depresión a lo largo del año 2024. Plataforma del Estado Peruano. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/1088925-establecimientos-del-minsa-atendieron-mas-de-250-000-casos-dedepresion-a-lo-largo-del-ano-2024

Montorio, I., Fernández, M., López., A & Sánchez, M. (1998).

La entrevista de carga del cuidador. Utilidad y validez del concepto de carga. Revista

Psicologica, 229-248.

Muñoz, G., & Enrique, G. (2020). Diseño de un taller para

cuidadores informales de adultos mayores del Servicio de Medicina en Hospital

Dr. Sótero del Río. Revista Vida,

99-109. http://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12972.48003

National Health Service (NHS). (2024). Quality and

Outcomes Framework (QOF): Guidance for 2024/25. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/

Nah, S., Martire, L. M., & Zhaoyang,

R. (2022). Perceived gratitude, role overload, and mental health among spousal

caregivers of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77(2),

295-299. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab086

Oleas Rodríguez, D. A., Yong

Peña, C., Garza Olivares, X., Teixeira Filho, F. S., Lucero Córdova, J. E.,

& Salas Naranjo, A. J. (2024). Emotional Coping Strategies for

Informal Caregivers of Hospitalized Patients: A Study of Distress and Overload.

Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 725-734. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S443200

Otzen, T., & Manterola, C. (2017). Técnicas de Muestreo sobre una Población a Estudio. Int. J. Morphol, 227-232. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022017000100037

Pan American Health Organization (2023). Salud mental:

https://www.paho.org/es/temas/salud-mental

Peng, Y., Xu, Y., Yue, L., Chen, F., Wang, J., &

Sun, G. (2023). Resilience in informal caregivers of patients with heart

failure in China: exploring influencing factors and identifying the paths. Psychology

Research and Behavior Management, 1097-1107. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S405217

Pina, S., Kousoulis, A. A.,

& Spandler, H. (2024). ‘Severe mental

illness’: Uses of this term in physical health support policy, primary care

practice, and academic discourses in the United Kingdom. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06048-4

Ramírez-Coronel, A. A., Malo-Larrea, A.,

Martínez-Suarez, P. C., Montánchez-Torres, M. L., Torracchi-Carrasco, E., &

González-León, F. M. (2020). Origen, evolución e investigaciones sobre la

Calidad de Vida: Revisión Sistemática. Archivos venezolanos de farmacología y

terapéutica, 39(8), 954-959. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4543649

Ramos, F., Morales, S., & Henao-Castaño, M. (2023).

Funcionalidad familiar y sobrecarga de cuidador según grado de dependencia del

adulto mayor. Presencia, e14373.

Rogero García, J. (2010). Los

tiempos del cuidado: El impacto de la dependencia de los mayores en la vida

cotidiana de sus cuidadores. IMSERSO.

Sánchez-Herrera, B., Carrillo-González, G. M., Chaparro-Díaz, L.,

Carreño, S. P., & Gómez, O. J. (2016). Concepto carga en los modelos

teóricos sobre enfermedad crónica: Revisión sistemática. Revista de Salud

Pública (Bogotá), 18(6), 976–985. https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.v18n6.53210

Shin, C., & Johnson, M. (1978). Avowed happiness

as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research,

5, 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00352944

Tang, F., Jang, H., Lingler,

J., Tamres, L., & Erlen, J. (2015). Stressors and

caregivers’ depression: Multiple mediators of self-efficacy, social support,

and problem-solving skill. Social Work in Health

Care, 54(7), 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2015.1054058

Tripodoro, V. A., Veloso, V., & Llanos, V. (2015). Sobrecarga del cuidador principal de pacientes en cuidados

paliativos. Argumentos. Revista de Crítica Social, (17), 213-231.

Valcárcel-Nazco, C., Ramallo-Fariña, Y., Linertová,

R., Ramos-Goñi, M., García-Pérez, L., & Serrano-Aguilar, P. (2022). Health-Related Quality of Life and Perceived Burden of

Informal Caregivers of Patients with Rare Diseases in Selected European

Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 19(13), 8208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138208.

Veenhoven, R. (1994). El estudio de la satisfacción con la vida. Intervención

Psicosocial, 3(8), 87-116. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/16195

Vilà-Baños,

R., Torrado-Fonseca, M., & Reguant-Alvarez, M.

(2019). Análisis de regresión lineal múltiple con SPSS: Un ejemplo práctico. REIRE

Revista d'Innovació i Recerca en Educació,

12(2), 1-10.

Vilca, L., Chávez, B., Fernandez, Y.,

& Caycho, T. (2022). Spanish

version of the revised Mental Health Inventory-5 (R-MHI-5): New Psychometric

Evidence from the Classical Test Theory (CTT) and the Item Response Theory

Perspective (IRT). Trends in Psychology, 30, 111-128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00107-w

World Health Organization (2022). Salud Mental; fortalecer nuestra respuesta. Organización Mundial

de la Salud. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

World Health Organization (2025, 30 de septiembre). Mental disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E., & Bach-Peterson, J.

(1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The

Gerontologist, 20(6), 649–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/20.6.649

Zenteno, A., Cid, P., & Saez, K. (2017). Autoeficacia del cuidador familiar de la persona en estado

crítico. Enfermería Universitaria, 14(3), 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reu.2017.05.001

Zwar, L., König, H., & Hajek, A.

(2023). Gender differences in

mental health, quality of life, and caregiver burden among informal caregivers

during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: A representative,

population-based study. Gerontology, 69(2), 149-162. https://doi.org/10.1159/000523846